.

.

People from the past

| 1750 # | old name, size | 1863 # | farm name | notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Säter, Gumjans 6 trög | 1 | Gumjans 6 trög | all farms in later naming noted to be in Kyrkbyn, no distinction between Sunnanå and Säter |

| 2 | Säter, Jo Påls 6 trög | 2 | Jo Påls 6 trög | Established 1695 |

| 3 | Mon, Västmon 18 trög | 3 | Mon, Västmon (9 trög) | subdivided again in 1890, 4 1/2 trög |

| s3 | Blomqvists | 1890 Blomqvists got 4 1/2 trög | ||

| 4 | Ol Sjuls, 3 trög | Est. 1758,former s3, originally a torp of Mon | ||

| 4 | Nyåkern 9 trög | 6 | Nyåkern, 9 trög | In 1600’s part of a farm known as Tryggården. There was an s6 by 1870, a small 1 1/2 trög subproperty |

| 5 | Gunnars 10 1/2 trög | 8 | Gunnars, 10 1/2 trög | Gunnars and Svens one farm of 21 trög, divided in 1680’s between brothers Gunnar and Sven |

| 6 | Svens 10 1/2 trög | 7 | Svens, 10 1/2 trög | subdivided pre 1860 but reverted to one for a time, then subdivided again by 1880.Svensbacken, Prinsbacken |

| 7 | Jonk 6 trög | 9 | Jonk, 6 to 8 trög | at one time twice as big |

| 8 | Olagården 18 trög | 10 | Olagården 9 trög | divided about 1734 |

| 11 | Bjurs 9 trög | Former s8, half of original Olagården | ||

| 9 | Öst på Mon, Östmon, 12 trög | 14 | Östigårn 6 trög | divided in 1758 |

| 15 | Nygården 6 trög | former s9, divided from Öst på Mon | ||

| 10 | Öst på Mon 9 trög | 12 | Sjuls 4 1/2 trög | divided in 1785 |

| 13 | Klockars 4 1/2 trög | formerly s10 (from Öst på Mon) | ||

| 11 | Skugg in Sunnanå, 9 trög | 18 | Skugg 6 trög | Skugg 11 and 12 were one farm, divided around 1700. Second division in 1846 |

| 17 | Bäcken 3-6 trög | former s11, from Skugg | ||

| 12 | Skugg in Sunnanå, 9 trög | 19 | Eskils 4 1/2 trög | one farm with 11 until 1700. Divided again 1841 |

| 16 | Gommerstroa 4 1/2 trög | formerly s12, divided 1841 | ||

| 13 | Nils, 6 trög | 20 | Nils, 6-8 trög | split in two by 1880 |

| 14 | Budd, Österbödd 9 trög | 21 | Österbödd 9 trög | in Sunnanå, both Budd farms were one until about 1670 |

| 15 | Budd, Västerbödd 9 trög | 22 | Västerbödd 6 trög | Sunnanå, subdivision 1836 |

| 23 | Hästraa 4 1/2 trög | Former s15, original old torp not lived in, resettled about 1836 | ||

| 16 | Ol Lars in Säter 10 1/2 trög | 28 | Ol Lars 3 trög | 16 and 17 divided in late 1600’s |

| 24 | Nylandet 2 1/2 trög | formerly s16,originally a torp turned to small farm | ||

| 25 | Hea or Heden 5 trög | Säter, formerly ss16, divided in 1854 from Ol Lars | ||

| 17 | Oppigårn in Säter 10 1/2 trög | 27 | Oppigårn 5 1/4 trög | |

| 26 | Täkta, 5 trög | formerly s17, founded 1833 originally a torp | ||

| 18 | Säter, Holmen 2 trög | 5 | Holmen, 2 trög | probable torp turned small farm in 1600’s, origin unknown |

| 19 | Bratthögen 6 trög | — | Most likely originally a torp from Östigårn, gifted 1755. By 1863 land incorporated into other farms |

In this section we hope to give a bit more of a picture of life in the old days, and perhaps a few glimpses of your ancestors.

Swedish names: Patronyms and Tradition

Sweden used patronyms instead of surnames until around 1900 when all had to adopt a permanent surname. A patronym was the name of one’s father, ie. Olof’s son and daughter used the patronyms Olofsson or Olofsdotter all of their lives. Women’s patronym didn’t change with marriage. There were also strong naming traditions dictating a child’s first name. Some names were especially well used, such has Jon, Olof and Per. This could mean a lot of people in a small town could have the same name. One was better known by their nickname, which often included where they lived or their occupation, plus a shortened or variation on pronunciation of their given name.

Spelling was far from uniform in the older days so the same person’s name could be spelled in different ways, depending on who wrote it. Many people were illiterate so they didn’t necessarily choose how it was written. A name like Per could be spelled Pehr, Pär, Petter, Päder or even Petrus. The way words were spelled also evolved. In old Swedish and Norwegian, the ”v” was often fv or hv. V was used instead of u in some words (eg. the name Blomqvist). C and K were often interchanged (Carin, Karin and Kerstin, Chiersten, Erik, Eric, Erick) Priests also wrote patronyms in short form, ie. Eriksson as Ersson,

Naming traditions can help us in some cases if the family name is less common. For example, a man named Sven Esbjörnsson would name his son after his father, so his first son would be Esbjörn Svensson. First sons had first right to a father’s farm. So, generations can be shown by their names. This is more difficult with more common names as there could be a number of peolple with the same name, or a name like Per Persson. It can be complicated as well by the sad fact that many children died. The dead child’s name was often given to a later born baby. Soldiers and priests took surnames however as they trained away from their parish, and there needed to be a clearer way to identify who was who. The traditions around first names were weakening by the later 1800’s, where we see different ”new” names and the giving of two names become common.

By the late 1800’s some Swedes already decided on a surname and in 1901 it became law. One had to choose his surname. The father’s patronym was often chosen, as were names including details of where they lived or features of nature, such as Bergman (mountain man), Sjöstrom (lake stream) etc.

Many of the emigrants we look at from Överhogdal were still using patronyms when they arrived in the New World, and they needed to decide on a surname earlier than those at ”home” . Many anglicized the father’s patronym, turning a patronym like Jonsson to Johnson. Others took a name which reminded them of where they came from. For this reason, siblings do not necessarily have the same surname.

Farm names

Where a person came from was very important in part due to the naming rules and there were no addresses as such. Farms and torps (crofts) were given names. The priests used a number system to organize their parish affairs, but these were not addresses and not used in daily speech by the villagers. The first numbering I am aware of happened around 1750, and at that time there were 18 farms. Some of these had already been subdivided from larger farms so were given their own numbers. As the years passed, more and more subdivision happened and the ”new” place was called a subfarm, and given an s#. There were so many ”s” farms by 1863 that they renumbered the farms and there were now 28. The chart shows the original farm number from 1750 on the left with the name it was known by, then the second 1863 numbering, and the subdivided farms by name. The 1850 numbers are out of order from the first numbering. I also included the measurement of farm size that was used, the trög. A trög is a measure of cultivated land and therefore of farm production. I add them just to give an idea of the size of the farm. A very large farm in this area due to the rough terrain was over 20 trög. The trög value could vary even without a subdivision.

A torpare (or crofter) was a farmer with the use of just enough land to have a cow or goat or two, a house and maybe a small field. He may or may not own the land he was on. If he had been a farmer for a few years (eg. married a widow and farmed until her son became of age) he could keep any new land he had broken during his time as farmer. (from Thomas) He might therefore own his small farm. I think this is why the total trög number does not always line up with the subdivisions. The torps were scattered throughout the village so it is hard or even impossible to know where they were. Torps were also given names. Råberget and Nybodarna are two such torp names. This list is taken from Frans Järnankar’s information on the farms and there could be other names that were used for these farms through the years. By looking at the farms over time one can see how they were becoming smaller and smaller and eventually many became too small to farm. By 1900 much of the farmland had been sold to the forest companies and there were only a few small farms left. The priests still used the numbering system but each number now indicated the dwellings lived in on the property which was once a farm. Some still owned their homes but many were renters and employed in forestry etc. I include this information because often the name of the farm is mentioned along with details about the emigrants.

The earliest known residents of Överhogdal

The priests working in Överhogdal began to make records of their congregants here in 1691. They created baptismal, death and marriage records, and in 1808 they started what they called household examination records, to keep track of communions taken etc. They are very useful for family historians looking back into the past as they give a serial record of who lived where. There are tax and court records from earlier in history and I include these names because I find it interesting to see the names of men who preceded the priests’ records.

In 1484, six farmers were mentioned in a deed which was drawn up regarding the Fagerflon hay field on the border with Turingen (Haverö area) These were (in old spelling) Byörn Sughurdhson, Halffward Olafson (probably the same person who brought the tithe of fish to Trondheim, see Överhogdal History), Redhar Thoreson, Hindrik Gwnnarson, Pawel Haerleffson, Torgardh Byörson. I wonder if the farm ”Bjurs” was previously owned by ”Björn” for example, similar to how ”Gumjans” came from the pronunciation of the name ”Gunbjörn”.

There are a surprising number of documents relating to events in Överhogdal which were found in the church. For example, in 1551 Oluff Jensson received ten marks, which constituted compensation for his inheritance in Sätern, which he had sold to his brother Esbjörn Jensson. Since Oluff did not have his own seal, Jacop Haluardsson in Sätern and Joen in Møn had to put their seals under the agreement as witnesses.

Around 1565 during the Nordic seven years war when Sweden had invaded Härjedalen, the following men were mentioned as residents of Överhogdal: Jonn at Moo (Mon), Henndrik Olsson, Gunnar Persson, Rolf Tryggesson, Oloff Halualsson, Biör Ionsson, Gunnar Olsson.

In 1600, these were the farmers on the tax roll:

Sven Esbjörnsson, Pehr Björnsson, Pehr Gunnarsson, Olof Halvarsson, Jöns Andersson, Olof Pehrsson, Hans Björnsson* Hans Gunnarsson*, Halvar Jonsson*, Pehr Eriksson*, Anders Olofsson*, Olof Andersson.* In 1611, those marked with an * were missing and there were two others, Pahl Eriksson, Jöns Bertilsson.

The village’s länsmen

The länsman was a local farmer who was given extra responsibilites. He was appointed to help maintain order in the village and he was the person higher government authorities would contact concerning various matters. It is not clear when Överhogdal had their first länsman, but probably long before the province became part of Sweden.

The job is certainly much older. A court penitent from Hedemarken in Norway in 1293 stipulated that (länsmen should be) ”sensible peasants, of known descent and well known in the community, with good repute and a will to do justice… but not the King’s henchmen” who were considered ”cunning and deceitful in their conduct”.

According to Wiki-Rötter, a länsman (later called a kronolänsman) was a local government servant who above all maintained order in a district and had some fiscal responsibility such as collecting taxes. In a royal resolution in 1675, it was stipulated that länsmen should be appointed by county governors “that they should be chosen from settled and well behaved farmers who live in the district, and not be anyone foreign or unsettled, who are unable to help the common people”. Their duties included tax collection and policing activities. In some cases a länsman could also be a prosecutor. He had fjärdingsmen (like a constable) as assistants, and the bailiff was his superior.

Their duties were not particularly well paid, but the later men must have enjoyed a certain tax exemption for their services in addition to their fees.

Only the tax rolls from the latter part of the 1500’s are available to help know who served as länsman in the parish. These show that in 1566 Jon in Mon was länsman, and two years later, they show that Rolf Tryggesson had this position. Sporadically recurring notes show that Olof Halvarsson was länsman in 1611 and Pehr Björnsson in 1625. While we know the names of these four farmers we do not know how long they each served. These are the only names we know from the Norwegian era.

When the Överhogdal länsman was arrested and taken to the Kårböle redoubt by the Swedes. (possibly Sven Esbjörnsson)

According to notes in Swedish tax records, the länsman in Överhogdal during the years 1645-1650 was Sven Esbjörnsson from the farm Svens. It is certainly possible that he took up the position a few years earlier when Överhogdal was still Norwegian and is the man mentioned in the following. The event takes place in 1644 when the border between Norway and Sweden ran in the forests between Över- and Ytterhogdal. Kårböle redoubt was Sweden’s outpost in western Hälsingland against Norway during their battle for Jämtland and Härjedalen. This is how the event is described in the booklet ”Kårböle redoubt, Hälsingland’s outpost in the West”, written by LL Lundh. (JJ translation)

During Major Francken’s time at the Kårböle redoubt, a rather funny incident took place there at his instigation. At the beginning of November, Francken sent a patrol to Överhogdal. The county magistrate arrested the länsman there and brought him home to Kårböle for questioning. The länsman would not admit to knowing anything about the enemy (ie. Norwegians and Danes) or military conditions in Norway. The Jämtlanders (and Härjedalens) lived in ignorance of the events of the war, he believed, because the Danish war leadership did not reveal anything. Over this silence of the Danes, the Jämtlanders had ”evil thoughts”, he added. When asked about the number of soldiers, he thought that all in all 2500 men could be counted in Norway and these occupied the most important places, such as Frösön, Gällösund, Brunflo, Rismyr and others. He thought Rismyr would have about 70 men. (Rismyr was near Älvros) Regarding other conditions, the länsman provided only vague and unclear information. After the interrogation, Francken arranged a small comedy for the länsman, says the war archivist Birger Steckzén in his interesting account ”The Battle of Jämtland 1644-1645” and from which work the following story is taken:

”An officer in question entered and declared that he had come with a message from Stockholm. Francken opened the letter, which contained an account of the naval victory at Fehmarn on 13 October, which he had his scribe read aloud, after which Francken and the Swedish officers thanked ”God for good tidings”. Tears came to the eyes of the länsman, and when Francken asked him what was up, he began to howl and curse the Danish king, who had never had any luck in any war, but still would not stay at home. After the man had been amply fed with food and drink and had been informed that peace was imminent, he was released and allowed to go back to his country again with all the news.”

Francken’s purpose (to inform the Norwegians that Denmark was losing) seems to have gone according to plan. The Danish authorities in Jämtland were soon forced to publish a similar story about a Danish victory, and at the same time encourage the common people with great promises, in order to counteract the news spread by the länsman. Francken, in his reports, complained of the difficulty of obtaining any knowledge of the enemy, for the people on both sides of the border were in collusion with each other. Francken further complained that the Forest Finns were hiding escaped knights.

Thomas Sievertsson told me that when the länsman returned home, the Norwegians realized how poorly fortified they were in Överhogdal and a redoubt was built on the North edge of town, where the farms Gumjans and Jo-Påls were later established. There were still signs of the stockade and of a fortification wall in the 1800’s. Per Eriksson who grew up at Gumjens took the surname Ringwall when he emigrated, as part of a fortification wall was visible in his day. There was also a swamp there known as Ringmyr. (circular wall swamp) The family at Jo-Påls, next to Gumjans took the surname Skanse in America, as some remains of the skans (stockade) were visible to them. The fortification was never used, as Sweden peacefully negotiated a settlement to claim Härjedalen and Jämtland.

OLOF PEHRSSON

According to the tax register for the year 1655, Olof from Olagården was länsman at that time. He was born in 1612 and apparently served as länsman on several occasions. He possibly took over the duties from Sven Esbjörnsson, but it is unknown in what year this happened. In 1689 he took on this position once again until 1692, probably taking it over from Esbjörn Gunnarsson.

JOEN ERIKSSON SKUGG

Joen was recorded as länsman during the years 1656 – 1658. He was 46 years old at the time of his appointment, according to what can be read from the parish’s burial book. The name suggests that he was a farmer at the farm Skugg.

JÖNS PEHRSSON

Recorded as länsman in 1659 and 1663. During the period 1648 to 1670 he was noted to be farmer of the homestead that later went by the name ”Ol Lars” and he probably died in 1670. Jöns is missing for some reason in the parish’s burial book and the date of birth is unknown. The farm ”Ol Lars” is the farm that in recent times has been called ”P O Bergströms”, if I (Per Göran) understand correctly.

ESBJÖRN GUNNARSSON

In 1679, a tax roll shows that the position of länsman was held by Esbjörn Gunnarsson. He was listed in this position for only this one year. Otherwise he was noted as the farmer of ”Gunnar’s”, the last time on the 1687 tax roll. In 1689 the länsman was Olof Pehrsson once again.

GUNBJÖRN OLOFSSON

He succeeded Olof Pehrsson and began his career as a länsman in 1693. All his predecessors in the job were owners of very large taxable farms, but this was not the case with Gunbjörn, who was the owner of the farm Gumjens. His homestead was originally taxed at only six trog, i.e. only about a third the size of the properties that his predecessors had been in possession of. He was listed for the last time as a county sheriff in the 1697 tax roll, but church documents show that he was länsman in 1701 as well. There is some evidence that Gunbjörn might have been a brother of Lars Olofsson, below, however this is not certain. He may have moved to the parish from elsewhere.

LARS OLOFSSON

Lars was the son of Olof Pehrsson, who was länsman until 1692 (listed earlier). He was noted as länsman from 1702 and held this office until 1719, when he resigned. The reason why he relinquished the duties of sheriff seems to have been suspicions of irregularities, which, however, apparently could never be proven. Lars became a farmer in Olagården after his father in the early 1690s.

Lars frequently appeared in older court documents. Sometimes it had to do with official matters and sometimes about purely private matters. In 1697, for example, he disputed with the county governor Påhl Engelbrektsson in Ytterhogdal about compensation for a moose hide that Lars had delivered. In 1707, he got in trouble because his cattle had grazed on the bog hay belonging to two farmers in Ytterhogdal.

ESBJÖRN SVENSSON

An old tradition was resumed when Esbjörn, farmer of Svens became länsman. There is different information about which year he took on the role, perhaps even taking it on as early as 1712, but in any case he was länsman in 1718-19.

Esbjörn was born in the year 1679 and was a respected man in Överhogdal. In addition to being a landowning farmer and länsman, he was also a member of the jury and a churchwarden. In addition to all these jobs he also served as Överhogdal’s innkeeper. His time was cut short however by his untimely death following an accident 5th September 1733.

Esbjörn was also a key man in Överhogdal during the Great Nordic War of 1700-1721, according to an article by Härjedalen author Erik J Bergstrom entitled ”Armfeldt’s soldiers and Överhogdal- on the 300-year anniversary” (publication OKNYTT number 3-4 2018).

This introduction is from his preface: ”Almost exactly 300 years ago, in August 1718, just over 10,000 soldiers marched under the command of Lieutenant General Carl Gustaf Armfeldt (1666–1736) from Duved in Jämtland to capture Trondheim. This attack was part of the Great Nordic War of 1700 –

1721. King Karl XII of Sweden was meanwhile at the fortress in Fredriksten inspecting the trenches on 30 November 1718 when he was killed by a bullet to the head. News of the King’s death was delayed, and Armfeldt did not receive orders to retreat until the end of December.”

“In January1719 the soldiers began their return march in biting cold over the mountains back to Sweden. The soldiers were caught in a blizzard and about 3000 died during the retreat on the mountains between Tydal and Handöl. Another 1,000 or so soldiers died of frostbite or were discharged from the military due to frostbite and consequent amputation. The retreat towards Handöl in Jämtland is often referred to as the death march of the Carolines.”

Esbjörn had a role at both the beginning and the end of this tragedy. From the article, in the summer In 1718, Överhogdal became a particularly well-used night camp for passing units heading to Duved. The Northern contract commander of both Härjedalen and Hälsingland had to make sure to deliver fodder and supplies for the village (to support the troops). The whole thing was overseen by Härjedalen’s commander Erik Elff and by the village’s länsman and innkeeper Esbjörn Svensson, both of whom were hard pressed. Överhogdal was also subjected for several years after the retreat to soldiers coming through. Esbjörn wrote in Sep 8, 1719 that he received one day’s advance warning of the arrival of the southern march and that he had to provide for both men and horses. ”I must have provision for 15 officers and 8 soldiers”. The arrivals were probably men who had ended up in captivity in Norway and who were finally released.”At this stage Esbjörn Svensson wrote to the governor and pleaded for repayment of his expenses and requested three barrels of tithe grain from Härjedalen or Hälsingland’s Northern Contract.” The article ends with: ”Things didn’t calm down until after the peace was restored in 1721”.

To understand the extent of the efforts Esbjörn and Överhogdal’s inhabitants had to go to one must read the whole article. I conclude with an excerpt from Erik J Bergström’s book ”Härjedalen’s lost sons”, page 108.

”When Armfelt’s retreat became a grim reality, Hugo Hamilton wrote on December 22 from Gävle and informed Elff about the army’s return, therefore he must bring resources to Överhogdal’s night camp, for example oats, fodder and chop for the horses. After all, a supply depot is supposed to have been set up in Överhogdal. The village’s small population under the leadership of länsman and innkeeper Esbjörn Svensson were thus subjected to severe and unimaginable stresses, both during the army’s advance, and during their pathetic retreat.” (taken from www.anhalten.se)

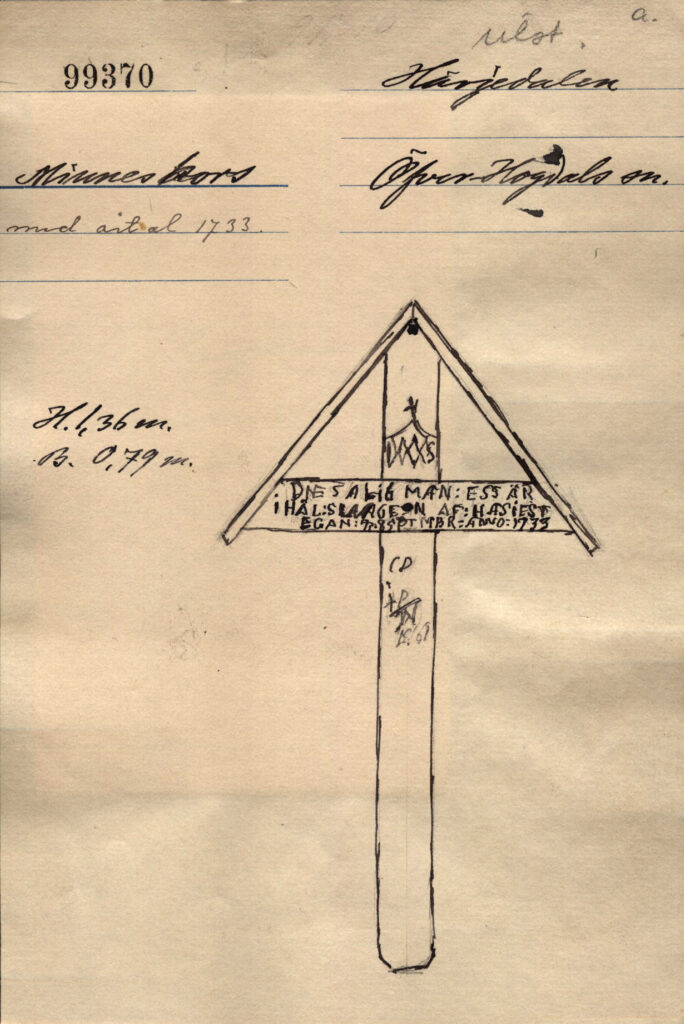

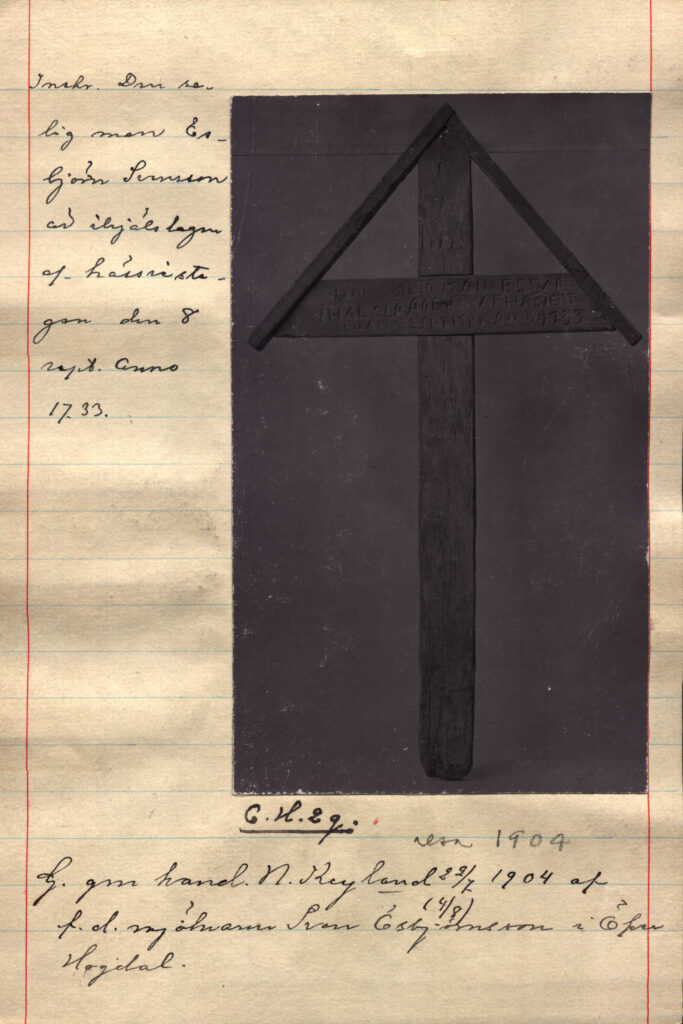

This cross was made in memory of Esbjörn Svensson. According to the museum’s guidebook from 1903-1904, the cross’s inscription reads: ”The upstanding man: E.S.S. was killed by rye ladders on 8 September in the year 1733”. (This date of death is not quite the same as recorded in the church’s death records.)

In 2011 Thomas Sievertsson made the following comments about the memorial cross on the Nordic Museum’s information https://digitaltmuseum.se that Esbjörns 5th great grandson Sven Esbjörnsson(1824-1917) had given to the museum. (as quoted at www.anhalten.se, translated JJ)

”Esbjörn died in the forest on September 5, 1733, when a number of rye hoist ladders fell on his head.

In Överhogdal, crosses were not normally erected over the deceased. Several 19th-century sources testify that the church, at least during the 19th century, lacked burial grounds (the oldest preserved one is from 1901). This memorial cross thus was not placed in the cemetery, but with all certainty it stood at the site where the death occurred…. According to unconfirmed information, Esbjörn’s accident took place on Digerberget (mountain) North of Överhogdal. This seems likely since the fäbod of his farm ”Svens” was in Knätten, which is near Digerberget. Therefore it is likely that the cross originally stood on the south side of Digerberget down towards Frägntjärn where a bog creates a natural opening into the forest.”

JÖNS OLOFSSON

After Esbjörn Svensson’s tragic death in 1733, Jöns Olofsson was chosen as his successor. Among all the people who have lived and worked in Överhogdal, there is no one who has left such rich court material behind him as Jöns Olofsson, and he is probably unparalleled in the entire province. Jöns held the position of länsman until 1753 when he was dismissed due to various forgeries.

Jöns was born in 1692 and apparently took over the Östgårn farm the same year he started a family. He is listed as responsible for the farm from the year 1718. The area where this homestead is located was in older times almost exclusively called Östmon or Öst på Mon. In modern times, the area is called Östmon, but I (Per Göran) do not know exactly which farm it is. Maybe the original farm no longer exists?

At first it seems that Jöns handled his duties as länsman and farmer in a reasonably acceptable manner. His area of activity was not always limited to Överhogdal, but occasionally also to the neighbouring parish of Älvros, where he collaborated with Crown Governor Pehr Olofsson at Vallen in Sveg. Frans Järnankar has in his documentation of Överhogdal 1600-1900 described Jöns’ escapades within the judicial system. Below is a brief account of some of the events.

”In 1746 he got into a quarrel with the old, blind, retired soldier Olof Svensson from the Nyåkern farm. It is unclear how the fight actually started, but during the incident, Jöns used some defamatory epithets that Olof Svensson was not happy with. As the länsman also resorted to ”wild threats”, the case was taken to court.”

That same year, 1746, Jöns fell out with the widow Brita Jonsdotter in Gunnars and her son Jon Esbjörnsson in connection with the creation of a few paths between the estates. Apparently there was no agreement on the ownership and the result was a real dispute where Jöns expressed himself in a way that absolutely did not suit the widow and son. The widow decided to nab the länsman and reported the incident for a decision at the court in Sveg. Both of the cases above came up at the autumn court the same year, but it turned out that Jöns had settled things amicably with both the soldier and the widow.

Another case that was taken up at the court in 1746 was much more serious. Jöns had been sued by the assistant priest Petter Festin and the offence was that on a couple of occasions he had been drunk during a church service. Jöns was in a drunken state ”going to confession” but had been turned away by Festin and in another case Jöns interrrupted and spoke out of turn during the time the confession of sin was being read.

Jöns defended himself by dismissing the whole thing as malicious slander, but a number of witnesses corroborated the priest’s claim. He then realized that he had to confess but explained that he had indeed taken one or at most a couple of drinks before attending the service, but that he had under no circumstances been drunk. Furthermore, Jöns said ”that in 1743 he had been stricken with “blood illness” and therefore used alcohol to alleviate his suffering. The sentence was a fine of ten riksdaler silver coins in addition to the usual church duty.

In 1747, Jöns was again summoned before the court, this time by Olof Svensson. Jön’s cattle had done damage to Olof’s land, including an area that was completely overgrazed. The result was that Jöns was sentenced to reimburse Olof Svensson with 30 pounds of hay and to replace a destroyed fence.

”In 1747, it was time again. Jöns was accused of being drunk during a church service at the home of widow Brita Jonsdotter. Jöns explained it all by saying that he had returned home from Sveg the same day and had been very tired and had terrible aches and pains, so that he appeared to be drunk. The district court ruled that Jöns be fined twenty-five daler silver coins. However, since it was determined that he was unable to pay without damaging his household and that his wife and children would suffer from a lack of food and subsistence, the sentence was changed. Jöns would be punished with eight days’ imprisonment, on water and bread only”. The above entries are but a fraction of länsman Jöns Olofsson’s escapades.

OLOF JÖNSSON ÖSTLUND

After Jöns Olofsson was dismissed in 1753, his son Olof Jönsson was elected as his successor. He was probably introduced to the task immediately after his father’s dismissal, but it is not entirely certain. The position may have been held by someone else for a very short period, but in that case it is unknown who served at that time.

Olof’s career as länsman was not as long as his father’s and was marked by constant setbacks. His finances were far from brilliant. The salaries of the 18th century were low and it was assumed that an official also had a decent income of other kinds in addition to the service. Therefore, farmers with a reasonably decent economy were usually recruited for these tasks. Olof seems to have been a sympathetic person despite major problems with his income. Social problems in general are not glimpsed at in the court records. He tried to sort it out but was unable to overcome the difficulties.

The first entries in the court records are from the end of 1756 when one of the creditors demanded money from him. It was a Johan Bergöö of Falun, but the background to the claim is not known. Bergöö considered himself to have a claim of 144 daler 18 öre copper coins. Östlund admitted part of the claim and declared that he was willing to pay it during the winter. But since he saw no way to pay the debts, he asked to serve the sentence on water and bread at Frösö prison house. He was therefore sentenced to sixteen days in prison on water and bread there.

Östlund’s chronic lack of liquid funds seems to run like a red thread through his time as länsman in Överhogdal. In most cases when he was in need of money, his eyes turned to his father’s property, to which Olof undeniably had certain rights. Olof seems to have been concerned about his father’s way of handling the farm and the debts he caused the family. His father’s creditors began to harass Olof with a request that he settle the debts of the homestead.

Over the years, a number of court hearings were held that shed light on Östlund’s precarious financial situation. The basic reason seems to be his father’s life, which finally resulted in Östlund being dismissed from the office, probably in 1763. Olof was married to Inga Brita Tollsten, who was from a priestly family in Forsa, Gävleborg. The church household records show she moved back to Forsa in 1766 from Överhogdal with her youngest children. Olof was working in Hedemora. From a note in the Forsa records, Olof died in Hedemora in 1770.

PAUL ROLFSSON DAHL

After Olof Östlund’s duties ended, Paul Rolfsson Dahl was elected as his successor. His father, Rolf Andersson, was a “klockaren” and it was natural that his son also followed in that occupation. Paul Dahl was married three times and had a total of eight children. In addition to his position as länsman, he had assignments as a lay judge and klockaren and was also farmer of the Holmen farm. Paul Dahl was possibly the last of the long line of parish länsmen in Överhogdal until the end of the 1700s. However during the 1800s and early 1900s, there were likely similar positions in the district.

A klockaren was an ecclesiastical office, which originally – in the Middle Ages – entailed the task of caring for the church and its furnishings and attending to the ringing of the bells.

In the 17th century, the ability to teach singing and lead the church choir began to be demanded of the klockaren where a special cantor did not exist. At the same time, he was also often tasked with teaching the youth to read and write. This meant that the job of bell ringer was often given to a priest. After the public school reform in 1842, the right to combine klockaren and school teacher service was granted. Likewise, the klockaren would often also be the organist, in churches where an organ was procured.” Wikipedia. I do not know if Paul held any of these other responsibilities.

A document from Överhogdal

In a letter from länsman Esbjörn Svensson in Överhogdal, we get an insight into the harsh conditions for the inhabitants of the village during the 1700s. The letter is probably addressed to County Governor Magnus Palmquist, who was County Governor of Gävleborg County in the years 1719-27, and is characterized by great submissiveness to the authorities. Esbjörn explains both his own situation as an innkeeper and that of the clergy and that the reason is that the inhabitants of the small parish have non-existent resources to support others than themselves.

The innkeeper was a heavy task for the poor farmers in the villages. It was a task that the inhabitants of the parishes had imposed on them by the Swedish authorities when its shameless henchmen travelled around the country so that they would have it as good as possible when they reaped tax revenues from impoverished people for the crown and their own well-being.

The priests also struggled to survive in the barren countryside, and from the letter if appears that several of them applied for resignation from their position due to the poor conditions in the parish.

The länsman implores the ”merciful elder” to give some aid with three barrels of grain from either Härjedalen or Ytterhogdal. What the result of this request is not known.

Here is an attempt to translate some of Esbjörns letter:.

There is a strong gap between Hälsingland and Jämtland and there is no reward for Innkeepers for their trouble and misery as elsewhere, nor can any help and support be had from the common people here in Överhogdal. The parish is small, only 18 poor farmers and crofters, so that none of them can take on being innkeepers, because it would make them destitute. Härjedalen is a difficult country and the farmers seldom get any useful grain, so the people have to take long journeys to buy it most years. This seed, which is required for life, must be honestly bought and procured every year.

The vicars of this country have their right to subsistence and grain (as well) if they will be able to reside in this difficult province and some may seek a humble resignation, so that they may graciously enjoy some retribution (as they would in a richer parish)

A legend on the naming of Härjedalen (Herjedahlen).

The province is supposedly named after a powerful Norse nobleman who had to flee over the mountains into Sweden when, in the court of Norwegian king Halfdan Svarte he killed one of the king’s men with a drinking horn during a drunken brawl. Thereafter he was known as Härjulf Hornbrytare (lit. ”Härjulf the Hornbreaker”) As a nobleman he soon found audience with King Anund of the Svea kingdom and entered into service for him. He fell in love with the King’s sister Helga while at the Palace. This displeased the King, and when Härjulf found out that the King was displeased, he said to his sweetheart: ‘I see two Kings after my head, so I will have to leave.’ His sweetheart said, ‘I will elope with you,’ and off they went – hundreds of miles up north into the forest and settled down in the area that would be named after him, Härjedalen, at a spot called Lillhärdal. Today a statue stands dedicated to them in this village. Härjulf and Helga were forefathers of the Icelander, Bjarni Herjólfsson, who was the first Norseman to see the ”new world” when he was blown off-course while on a voyage to Greenland. His boat is the one Leif Eriksson acquired about 15 years later for Leif’s famed landing on Vineland. (from Wikepedia and story told by Peter J Skanse to his family. Peter thought he might have royal origins due to an ancestor from Lillhärdal. This is certainly possible for many in Härjedalen given the many centuries between Härjulf and today!)