.

Överhogdals history

Överhogdal’s History

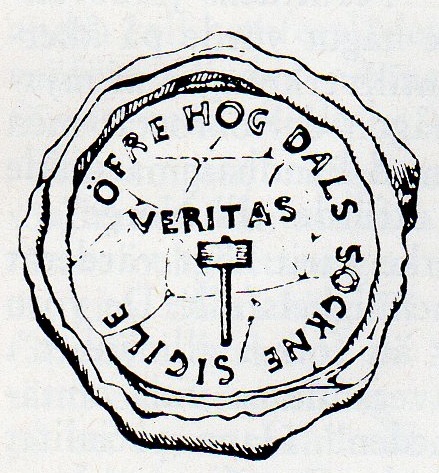

Överhogdal´s parish seal

Describing the history of Härjedalen and Överhogdal in particular, has been a challenge for those studying it. The early written material that is available is very inadequate and sometimes difficult to interpret, particularly in the case of documents drawn up by the Norwegian and Danish authorities. Due to the fact that Härjedalen belonged to Norway under Denmark before 1645 and that tax collection was usually handled by Norwegian bailiffs, today there is very little source material regarding the settlement of the village. Fortunately, a surprising number of documents and treasures were stored in the village’s small church. The most amazing discovery was the Överhogdal tapestries, now housed in the Jamtli museum in Östersund, but there are other deeds and bits of information that give a bit more of a glimpse into the history of the area.

Going way back in time, there is evidence that the land in Härjedalen was used by Stone age people. The first population of Härjedalen is estimated to have migrated here some 9000 years ago. The people hunted and fished and lived close to the inland ice which had then started to melt. Ruänden, in the Flatruet mountains in Northwestern Härjedalen is the location of a large site of rock paintings. These consist of about twenty figures depicting people, bear, moose and reindeer. The rock paintings were first reported in 1896 and are estimated to be over 4000 years old. (Wikipedia)

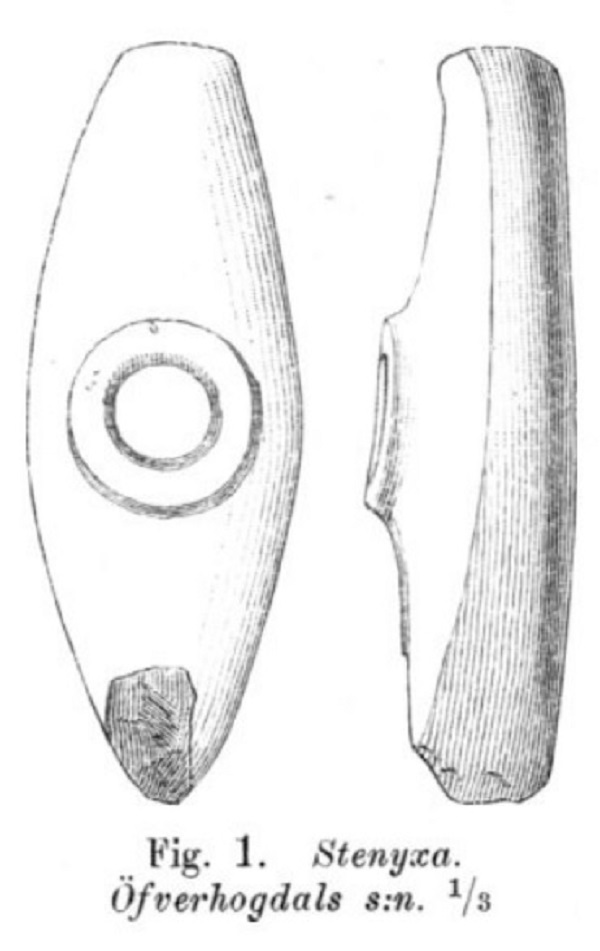

A stone age axe was found in the Hoa River. It is a so-called boat shaped axe with an extended handle hole, 16 cm long and 6 cm wide. The people using the land were nomadic, and may have been the predecessors of the Sámi, or Germanic peoples, or both. The Stone Age in the Nordic countries is usually said to begin about 12,000 BC when the first people wandered into the area, until about 1800 BC when bronze objects became increasingly common as status symbols and tools.

Relatively more recently but still ancient, an arrowhead was found in 1955 by Harry Olsson, East of Rosången Lake, on the West side of Staverberget. It is of a type that belongs to the late Viking Age, of a similar type to arrowheads found in Dalarna and Norrland, in hunting environments.

The question of where the first permanent settlers to Överhogdal came from is uncertain, but linguistically there are many similarities between the area’s original dialect and the Norwegian language. Erik Modin was a priest who worked in Ytterhogdal at the end of the 1800’s. He wrote in his book ”Härjedalen’s Place Names and Legends” that, according to tradition, the village’s first settlers came from present-day Norway. The path the first settlers took may have been via the valley of the Hoa River from the Jämtland side until they found places suitable for settlement. This may have happened at the end of the 11th century, when a major emigration eastwards from Norway is said to have taken place through the mountain passes East of Trondhiem.

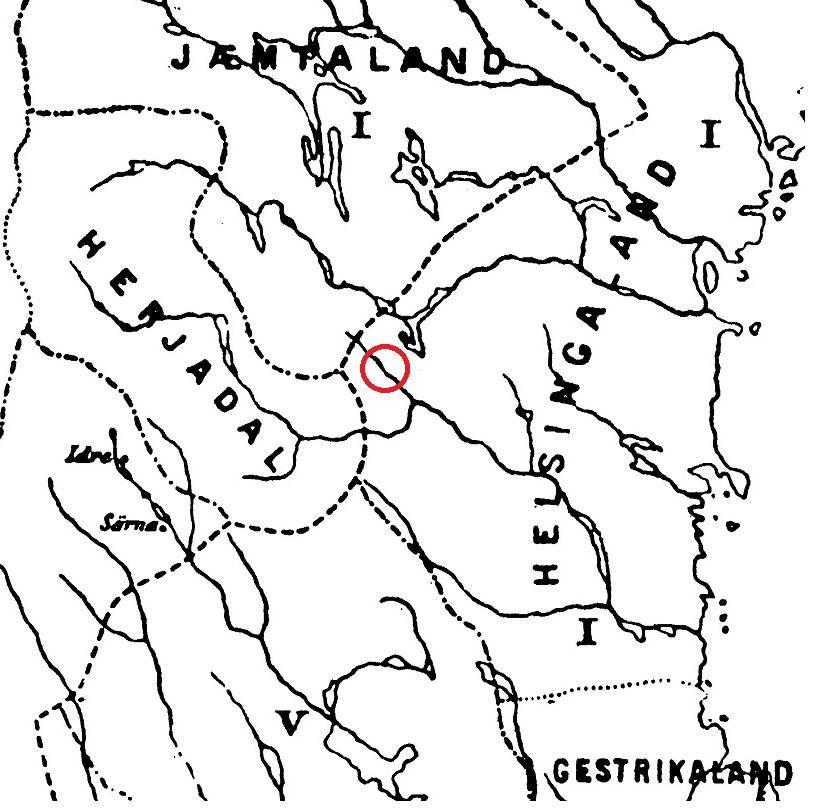

Sweden and Norway were divided into provinces many many years ago. Överhogdal lies within the old province of Härjedalen, close to the adjoining provinces of Hälsingland, Jämtland and Medelpad. For hundreds of years, Jämtland and Härjedalen were part of Norway. Norway itself was part of the Danish kingdom for many years. Hälsingland and Medelpad were always Swedish. This changed in 1645, when as part of a treaty settlement, Jämtland and Härjedalen were ceded to Sweden. In 1810, Jämtlands län, or county was formed, uniting the former provinces of Jämtland and Härjedalen under a common county governor.

Despite the history of Härjedalen once being part of Norway, Överhogdal itself is so close to the old border with Sweden that it may have been in Sweden at times. Snorri Sturalson, the Icelandic poet and historian who lived in the 1100’s, had a map in his book “Om Sverige ”(about Sweden) which suggests the Hoan valley was at that time part of Sweden. Other documents give conflicting information as to which side of the border Överhogdal lay on.

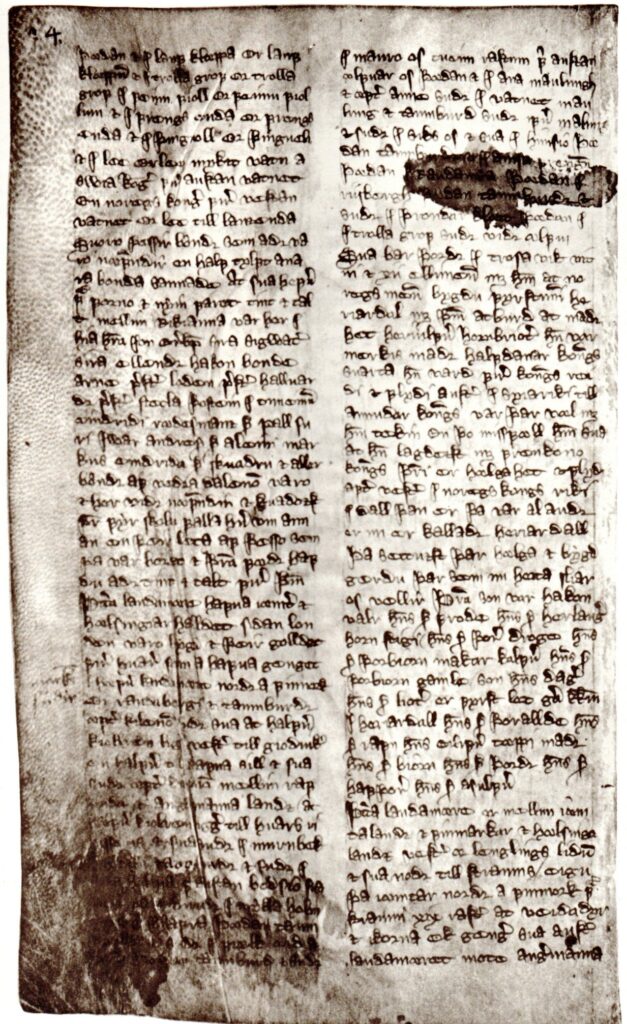

The earliest document concerning Härjedalen comes from a Norwegian-Swedish border meeting in 1273. Among other things, it mentions ”six farmers from the Upper Valley.” While there is not total agreement as to where this was, some think it refers to the upper part of the ”Hoa valley” ie. Överhogdal. This seems logical considering that the boundary line crossed between the two Hoadal parishes, the Upper and Outer Valleys. (Över and Ytter) In the document, Rosången and Runasten are mentioned as boundary marks.

Runsten (the rune stone) was the old boundary mark between Härjedalen/Hälsingland and Norway/Sweden. Today it is usually called the Skålsten (bowl stone) because of its bowl-like indentations. The name Rune stone does not refer to the old written language runes. Rune used to also refer to somewhat mysterious creations of nature.

Border conflicts

There were no legally established boundaries before the 1800s including between farm plots. Hay fields were important to farmers and the use of them was based on tradition between village neighbours. These conditions often led to disagreements and eventually created great difficulties that were only solved by the land parcels that were established in the early 1800s. In connection with these, permanent homestead boundaries and proper map material were created.

Despite this, the right of possession of the homesteads was regulated by law and confirmed by the district court. Birthright primarily applied if a homestead were to change owners. This meant that the closest relatives had the right of first refusal. The eldest son usually had this right to take over ownership, but taking it on could often be a burden, as it included having to care for elderly parents, unsupported sisters etc.

There might also be a draw between the siblings when it came to taking over a homestead. This drawing of lots could not be carried out without the consent of the district court, and was usually carried out before the court. The purchase prices were also monitored by the authorities and were usually determined after inspection and valuation, which was carried out by the county governor and a couple of lay judges. Countless disputes concerning the right to use hay fields were also dealt with at the court. In many cases, the dispute could be about hay fields that had been left as security for loans or similar debts, Not infrequently, the lender refused to let the borrower redeem the mortgage. These situations usually arose when the collateral was considered to have significantly greater value than the loan.

But disputes about the meadows and hunting grounds did not occur only among the villagers. For many centuries there were feuds with the neighbouring villages over hay fields; with Älvros, Rätan, Haverö, Ytterhogdal, Vitvattnet. The oldest known dispute about hay fields between Ytterhogdal and Överhogdal is said to have taken place in 1413. Överhogdal’s geographical location, bordering three other counties, meant that property disputes were inevitable.

The name Överhogdal existed at least in 1432, when Övre Hodal was written. In 1466 Öffre Hoodall is mentioned and in the 1564 tax register the name is Öffre hodals Sochn (socken, parish) In 1652 it was written as Öffwerhoodall and in 1771 they have ”modernized” the name to Öfwer-Hogdal.

One of the earliest mentions of someone from Överhogdal is Hauard Olafson (Halvar) who was mentioned in a letter written in 1470. It was said that he travelled to Trondheim to deliver the parish’s tithe. This consisted of six pounds of pike, which was acknowledged by Archbishop Olaf.

The Överhogdal church was an annex of the church in Sveg until 1812. From an ecclesiastical point of view, the parish was linked to the Diocese of Nidaros with its seat in Trondheim since the beginning of Christianity in the Nordic countries. The first chapel in Överhogdal was built by the villagers and was consecrated in 1466 during the Catholic era. Usually, church building was something that the Pope’s bishops financed in one way or another. This was not the case for our village, they financed it themselves. When the chapel was consecrated, there was likely no representative of the Catholic Church present in the village. However, the Catholic Church’s excessive lust for money was one reason why this poor community had to send a representative all the way to Trondheim to deliver gifts to the papacy’s representatives.

At least the receiving Archbishop Olaf, the Pope’s representative in the Nordic countries, had enough good sense to ”proclaim” that the residents of Överhogdal would in future not need to travel to Trondheim, but in future were to bring their tithe to the Överhogdal church. He recognized the absurdity of poor people having to walk close to 1000 km to provide the papal church with dried fish.

Years of Unrest

The beginning of the 1560s was characterized by frequent disputes, especially regarding hay fields, but also regarding hunting and fishing rights. Ytterhogdal’s villagers, especially farmers in Västansjö (closest part to Överhogdal), claimed land that was significantly further west than what was allowed according to the country guilds. Around the year 1562, some farmers from Västansjö clashed with those from Överhogdal at the upper end of the village, on the spit of land that exists between Hoan and Vitalman. It is quite clear that the farmers of Västansjö counted this land as among their rightful domains. The dispute was perhaps not so unusual, considering that in the past, people from Hälsingland made inroads much deeper into Härjedalen, intent on plundering.

The Nordic Seven Years’ War, 1564-1571

While Jämtland and Härjedalen may have had less than desirable farmland, their location close to the Gulf of Bothnia led to years of unrest. The so-called Nordic Seven Years’ War was between Swedish King Erik XIV and Danish king Frederick II. Härjedalen and Jämtland were Norwegian, but seen as strategically important for Sweden to occupy, since the Swedes were concerned about a Danish attack from the Gulf of Bothnia which could cut off their northern Swedish provinces. Sweden felt it could prevent this by occupying Härjedalen and Jämtland, so that it did. After this period of war, the provinces returned to being Norwegian. The peasantry however were worried about possible reprisals from the Norwegian authorities because they had sworn an oath of allegiance to the Swedish king (in order to survive the invasion). Those fears turned out to be unfounded. Those who wanted to continue their Swedish affiliation were given permission to move to the Swedish side of the border. Whether anyone accepted that offer is unknown, but unlikely.

The Baltzar Feud

After this war ended, there was apparently relative calm for the next 30-year period, except for recurring fights and quarrels over hay fields with the neighbouring parishes. The closest Norwegian authorities were based in Hackås and Frösön (near Östersund), but they did not bother the people of Överhogdal more than necessary, and it was not often. Tax collection was taken care of by the bailiff who was stationed in Sveg and the village länsman knew to be on good terms with his neighbours.

However, a decade into the 1600s, unrest began once again. The events that occured were later called the Baltzar Feud; armed conflict in Jämtland and Härjedalen which was part of the Kalmar War of 1611-1613. The person who bore the ultimate responsibility for what happened in the area was the German-born Finnish nobleman and colonel Baltzar Bäck, who came to the fore of the war events in Norrland in the spring and early summer of 1611. Since 1607, Bäck held a position as governor of Lapland, where his main task was to guard the Swedish crown’s tax rights. At the end of January 1611, Jacob Tommesson had orders to attack Jämtland and Härjedalen with a force of men from Dalarna. To help him with this, Bäck was also ordered to enter these provinces with the Västerbotten knights together with a detachment of Poles and men from Hälsingland.

At the beginning of August 1611, Bäck and his men were camped in Stavre in southeastern Jämtland. From there he wrote another letter to the Jämtlanders in which he emphasized the futility of this war and explained that the Danes’ prospects of surviving this war were practically non-existent. The letter was distributed in a large number of copies and possibly contributed to the Jämtlanders’ reluctance to defend themselves. In any case, the letter seems to have influenced many, both in Jämtland and Härjedalen, who willingly volunteered as scouts, guides and advisors to the Swedish troops.

There is a local legend about Ragnhild who fled up to Lövberget where she hid in a cave next to one of Sweden’s largest boulders, accused of smuggling weapons to the Norwegians, The Swedes planned to capture her and no doubt execute her, so she fled. She hid in the cave with two goats and survived with the help of some of the villagers. Since then the stone and the cave bear her name. Perhaps this event occured during this war.

Bäck’s knights soon flooded the entire province, where they often behaved brutally towards the peasants. Many farmers in Härjedalen therefore fled with their families from their homes to take refuge further into Norway. Whether anyone fled from Överhogdal is not known, but it is certainly a possibility.

The conquest of Jämtland seems to have gone surprisingly fast. Already on August 15, the whole of central Jämtland had surrendered without any significant resistance and a couple of weeks later it was Härjedalen’s turn. The person who was given the closest oversight of Härjedalen was Olof Ingemarsson, and the people of Härjedalen showed from the beginning that they were cooperating with the invaders.

In the autumn of 1611, twelve peasant men from different parishes in Härjedalen signed an oath of allegiance to the Swedish crown in the Älvros church. The deed was signed on 3 September 1611 and those who put their name were four from Kolsätt, one from Backen(?), four from Lillhärdal, one from Ytterberg and one from Älvros. By signing the document, they swore on behalf of their villages ”loyalty, fidelity and manhood with life, goods and blood” to the Swedish king and the government.

Despite this, the Swedish warriors continued to torment the population. In a long letter dated in Sveg on 20 January 1612, during Gustav II Adolf’s reign, the common people described the situation. It told how the poor population continued to be tormented by the Swedish soldiers and their colonels who ”raped and robbed and torched the principal district, which consisted of 57 farms”. This happened despite the fact that they had assured the Swedish crown of their allegiance and promised not to ”fall against them” and to which Olof Ingemarsson on behalf of the invading army had agreed to. Finally, in 1613 a new peace treaty ended the hostilities. Jämtland and Härjedalen were once again under Danish/Norwegian rule.

1645- the Treaty of Brömsebro

At the beginning of the 1640s, Sweden was a political and military superpower, while its hereditary enemy, Denmark, was weak and had no allies. After the Danish fleet was defeated by a Swedish-Dutch squadron at the Battle of Fehmarn in October 1644, Denmark was completely defenceless. Swedish troops, under Queen Kristina had entered Jämtland as well as other Norwegian provinces in the South but for some reason rather than fighting, they started the negotiations which led to Härjedalen and Jämtland becoming Swedish provinces.

The peace treaty of Brömsebro came about as the result of negotiations between Sweden and Denmark which were conducted from February to August 1645, ending the hostilities between them. The peace treaty was signed under French mediation after very lengthy negotiations, and was comprised of 46 points. The Swedish chief negotiator was Axel Oxenstierna and for Denmark was Korfitz Ulfeldt. Major issues of dispute were shipping, customs fees in Öresund and Bälten, and the ownership of the provinces of Skåne, Blekinge and Halland. Jämtland and Härjedalen seem to have been a fairly small pawn in the negotiation game. This is illustrated by Oxenstierna’s statement that ”the provinces of Jämtland and Härjedalen were regions filled with cliffs and swamps and were therefore not worth much”. The course of history would have been different if these provinces remained Norwegian, but we can only speculate on this.

After the peace treaty was signed in August, the Swedes formally took over the provinces and received oaths of allegiance from the people. Johan Berndes, vice president of the Mining College was ordered by royal letter to hurry through day and night to Jämtland to receive Jämtland and Härjedalen, occupy the redoubts and examine the boundaries and land records. This he did by early November. However there were no representatives from Härjedalen at this meeting in Frösön. It was several weeks later when when Mining Master Lybecker for Sweden and Captain Erik Blix for Denmark were sent to Härjedalen to give an account of the contents of the peace treaty to representatives of the population. Berndes was probably also present.

On 15 November, the two priests of the province, three county governors and the lawmakers of the three district courts signed the oaths in Sveg’s vicarage. At this time, Härjedalen had three district courts: Sveg, Lillhärdal and Hede. In the documents that were drawn up, the domicile of each signatory is stated, and it does not seem that anyone from Överhogdal was present.

Life in Överhogdal

Överhogdal’s population has never been large; the thin soil, limited fields and rock covered countryside make it a difficult land to grow crops. From what Thomas told me, there is evidence suggesting there were seven farms established in Överhogdal when the Black Death (bubonic plague) ravaged Europe between 1348-1350. It appears only one farm survived this catastrophe. In time these empty farms were taken up either by younger brothers or through internal migration. A land deed from 1484 mentioned six farmers in Överhogdal, which was likely the total. During the Swedish occupation period in the 1570’s, seven names were mentioned. Thirty years later when Härjedalen was once again Norwegian, the tax roll listed twelve men. In 1611, eleven years later, only six of the same men were mentioned, plus two more. The fact that so many dropped off the tax rolls between the years 1600 to 1611 may be that they for some reason became exempt from tax. But one cannot rule out that they ”disappeared” because it was a time of unrest.

There are some interesting descriptions of life in Överhogdal that have survived through time. The following excerpts come from a translation of old Swedish by Per Göran Björk, then a translation into English by Janet, so there may be inaccuracies. However, they still give some interesting glimpses into life hundreds of years ago.

Description from 1737, Sparenborg and Jöns Olofsson

In July 1737, the governor of Västernorrland County – to which Härjedalen belonged at the time – sent a letter to the authorities in the counties he oversaw with a request to give an account of various areas of industry. Commander P. Sparenborg put together the compilation from the various parishes. His information came from the local länsmen (similar to sheriffs) and in Överhogdal the länsman was Jöns Olofsson. (there is more information about Jöns in the section on People from the Past; he was a colourful character!). Below are shortened descriptions from both men.

Sparenborg’s report:

Överhogdal’s annex (annex of the larger church in Sveg), is a small wooden church, and (the village) is named after the river Hogan or Högan, Hofvan or Hoan and is called Överhogdal in reference to Ytterhogdal in Hälsingland; Located northeast of the mother church 45 km miles but in winter 60 km. Since the country was under Norway,’s rule they often felt the effects of hostilities. It is a small place and lies very close to the border with Hälsingland.

Summary of länsman Jöns Olofsson’s report

After a flattering introduction to his report, to say the least, Olofsson describes the village.

“Överhogdal has its name from the river Hoan (Hofvan) which has its origin in a spring closest to Klövsjöfjällen, which is located and stretches towards the Norwegian mountains, and which runs through Överhogdal and to Ytterhogdal. Överhogdal is located northeast of Sveg, our mother church, and borders three other counties, namely first Ytterhogdal parish in Hälsingland, 15 km southeast of Överhogdal’s forest, and according to old men’s stories, there the National border ran between Sweden and Norway”.

“The next parish church is in Rätan, 30 km, but the border (with Jämtland) runs about 7 km from Överhogdal though a rough and stony forest, through which the main road comes from Jämtland to Hälsingland. To the east is Haverö parish with the distance running through the middle of the forest”.

“Other things to mention, there is nothing remarkable to report, neither with the church nor with anything else that the poor crofters inhabit… It is said that the reason why those who first settled this parish did is they saw grass growing on the banks of Hoan. However, one must now consider that in our country most things that can go wrong do. Therefore, in order to survive they do rough work, looking for bog ore which is forged, and may have some market…. at the Norwegian border or towns. Furthermore, no useful ore can be spoken of by either old or young. Otherwise, there is nothing remarkable to write about this small parish”.

Överhogdal in the later1700s according to A.A. Hülphers

(Abraham Abrahamsson Hülphers 1732-1798 was a topographer, music historian and genealogist)

Överhogdal’s church was rebuilt in 1740 and the interior totally repainted. A new bell tower was erected in 1768. One is able to attend church services several times, namely the 13th day of Christmas and the following Sunday. Otherwise five Sundays a year, although the sermon is always given on the previous Saturday.

Agriculture and especially cattle farming are of small scale and grain must be bought from outside in years with poor yield. The home fields here are said to be more prone to frost, which is why several areas of cultivation have begun in the highlands in recent years, to the west and north from the village. Cattle farming provides little income through the sale of cattle, butter and cheese. Other activities are hunting and fishing.

In the absence of a route for log rafts, the parish cannot get any profit from the forest by selling timber to the Lottefors sawmill in Hälsingland as it can in the neighbouring parish of Ytterhogdal. Some here suggest the Hoa River is suitable for floating logs, but those with more experience say that areas are too shallow and narrow for this to be viable. In the summer, Överhogdal is 45 km from Sveg down a difficult path. In the winter, when it is not possible to travel the most direct route due to heavy snow, travellers have to go through Ytterhogdal and Älvros, making it a 60 km trip.

In 1765 there were 162 people living in Överhogdal parish, three years later 151 and in 1773 the number had decreased to 123. (no known cause for the drop in population)

By the crown länsman Olof Dalin on 18 January 1821.

(older spelling of places maintained) Öfwerhogdal parish forms the north-eastern part of Herjeådalen. It is bordered to the north by Rätan parish in Jemtland, to the north by Hafverö parish in Medelpad, to the east by Ytterhogdal parish in northern Helsingland, to the south by Elfros and to the south by Sweg parish in Herjeådalen.

The area of the parish is approximately 25-30 square km. Within this perimeter are three lakes, namely Rosången, Lången and Linsjön. Rosången, the largest, is situated 2.5 km to the north, is about 38 km long and 2.5 km wide. Most of it is surrounded by stony ground, stones (often boulders) beside stones, stones on stones, except for a few small bogs and marshlands.

The smaller part of Lången, which is situated at the boundary of Ytterhogdal parish, belongs to Öfverhogdal. Linsjön is small; it is located at the far end of the area of Elfro parish. In addition, there are smaller lakes, which come under the name of ponds, of which of different sizes are in number more than 20. In these lakes and ponds there are no other kinds of fish than pike, perch and roach, and seldom any burbot. In Linsjön there are some small salmon trout in addition to the perch.

At Håttersåhn, which lies in undeveloped land towards Rätan, the inhabitants of Öfverhogdal own half the lake, where they fish for small whitefish in the autumn season. On the whole, fishing is not very profitable in view of the small yield, therefore in later times the desire to fish has diminished.

The parish itself is situated between two rock covered mountains, in the valley of the Hoa river which in the spring and with falling rain flows considerably, and the meadows situated there experience good growth of grass (for hay), which is the main reason the homesteaders’ can exist here.

The arable land (to grow crops other than hay) on the other hand, is quite light and very dry peatland, in a frost-prone climate; therefore up until the 1750’s farmers up did not attach any value to the cultivation of arable land, but worked more on producing iron from bog ore. Some of this iron was sold in raw form, but most of it was worked with a hand-hammer forging, into sinking stones (fishing weights) and large cauldrons which were exported to Norway. The Norwegians were quite keen on sinking stones for their fishing gear and the cauldrons to boil salt in, which is why they were also called salt cauldrons.

As crop production was thus abandoned, grain had to be procured annually for cooking flour, and most of it from the towns at a distance of 175 to 195 km. Pine bark flour was almost constantly used (as a poor substitute). Later, especially since 1760, agricultural use of the land began to increase as swamps were drained and cultivated into fields which became more fertile than the old fields, especially suitable for sowing flax and for hay growth. Winter or autumn rye sowing seemed to have the best success on the old dry Hodal soil.

The parish was an annex parish under the diocese of Härnösand, under the pastorate of Sveg, but by the Gracious Resolution of the King of December 9, 1812, was separated and added to the parish of Ytterhogdal in Helsingland with all priestly services. In former times, ordinary services were held 6 Sundays a year and the Saturdays the day before, when the pastor from Sveg had 45 km to travel in the summer, but 60 km in the Winter, and the Ministers who lived in Lillherdal had 90 km to travel in the winter.

The church is of wood and was rebuilt in 1744, decorated with sculptor’s work on the pulpit and the altarpiece is gilded and painted. The walls are painted scenes of Jesus’ most remarkable wanderings on earth, and the roof is decorated with paintings depicting air and clouds. There are two bells hanging in the wooden bell tower which was built in 1768.

According to the present land register, the parish contains … 181 trög of farm land (a trog is a measure of how much land a farmer could work in a day) and is inhabited by 21 farmers. At the beginning of 1821 the population of old and young, of both sexes is 200 persons.

On the whole, each person is driven by diligence and industry, and there is very little difference as to the type of work they do for profit. The majority have a reluctance to try new things or accept new businesses. It is a major shortcoming that no artificial fertilizer is produced.

The general way of life is frugal. Grain must be used sparely and the grain from the years with better crops is still not great, mixed with the chaff, This is general so no one is to be blamed. Bränwin (liquor) is not used daily in households, except on certain occasions and festivals, such as Christmas, Easter, Pentecost as well as Midsummer, Mickelsmäss and when the priest’s holiday occurs.

The temperament of the people is merry, and their pastime at specially awaited occasions, weddings and parties, is based on jokes that produce ridicule without disturbing the peace with each other. No one goes looking for a fight. It is particularly peaceful here in regards to robbery. In the parish there has been no thief in living memory. Handicrafts (ie. to sell) except for the needs of the household, are not practised. There is no opportunity here to make a profit. Of the abundant forest that is here, no sale can take place, for there is no place ot float out the logs. There are no signs of ore deposits.

Industry and Trade

Iron Production

Iron ore production was the main industry through many centuries, but it was not mined in the traditional ways. The iron came from the many bogs in the area. Bog iron is an interesting phenomenon. Streams carry dissolved iron from nearby mountains into the bogs. Bogs are marshy stagnant waters. The iron is concentrated by two processes. The bog environment is acidic, with a low concentration of dissolved oxygen. In this environment a chemical reaction forms insoluble iron compounds which precipitate out. This is aided by anaerobic bacteria (Gallionella and Leptothrix) growing under the surface of the bog that concentrate the iron as part of their life processes. The iron forms as nodules which can be harvested by cutting the turf and peeling it back. It is not high grade but it can be smelted.

There is plenty of bog iron in the Hogdal area, and the handling of it here was extensive. For the farmers, iron processing became an important source of income. In some villages, practically every farm had its own blasting furnace. There were many furnaces in the parishes of Sveg, Ytterhogdal, Älvros and Ängersjö especially, but iron production also went on here in Överhogdal. Härjedalen is referred to in older documents as ”the soot valleys” because of all the soot around the blasting furnaces.

The ability to process the bog ore was probably not developed by the farmers themselves. The knowledge may have been transmitted by the ethnic group that immigrated from the north-east and who are later referred to as Sami. The scale of iron production eventually became so large that it was possible to export. Large cauldrons and fishing weights were exported into Norway. Tools were of course also made for local use.

In connection with the reconstruction of the E45 highway in southern Överhogdal, an iron production site was investigated and removed in 1994. The blasting furnace was an ”Evenstad furnace”. Based on C14 analysis, it was ascertained that the furnace had been built in the 1300s. The C14 dating also showed that iron production had been going on at the site into the 1400s,

Cattle Farming

The other main occupation in the village from ancient times was cattle farming. They had a small, hardy breed known as fjällko. (mountain cow) These sturdy beasts could survive on sparse grazing lands and lean winter rations. The parish’s common grazing areas were the large expanses of forest outside the village’s cultivated pastures. In old times, summer pasture life flourished in Överhogdal. The cattle were numerous, and in 1769 there were reportedly 147 cows, 20 oxen, 40 horses, 200 goats, and 250 sheep divided among 22 farmers. The population was 150 people. Obviously from this list, livestock other than cattle were raised as well.

The women took the cattle up the hillsides where they could graze in the forest, and they and young children lived at the summer fäbod (cabin) while the men stayed in the village to gather firewood, make iron, harvest hay etc. As well as tending to the cows, the women kept busy making cheese, spinning, weaving and making clothes for their families.

Each herd usually consisted of four to ten cows. They would be free to graze in the forest during the day and then were called back with a special ”song” (kulning) in order to be milked. There would be a lead cow, who wore a bell to make it easier to find her if need be. Most of the time she would eagerly come when called, as she got a special treat and was eager to be fed and milked, and the other cows would follow her.

Trade

In older times, the population had little need to purchase supplies. Most of what they needed could be obtained through farm trade. Several in Överhogdal engaged in this over the years. Most food and clothing was produced by the villagers themselves, but eventually there were some itinerant peddlers who supplied the population with goods that were not produced in the village.

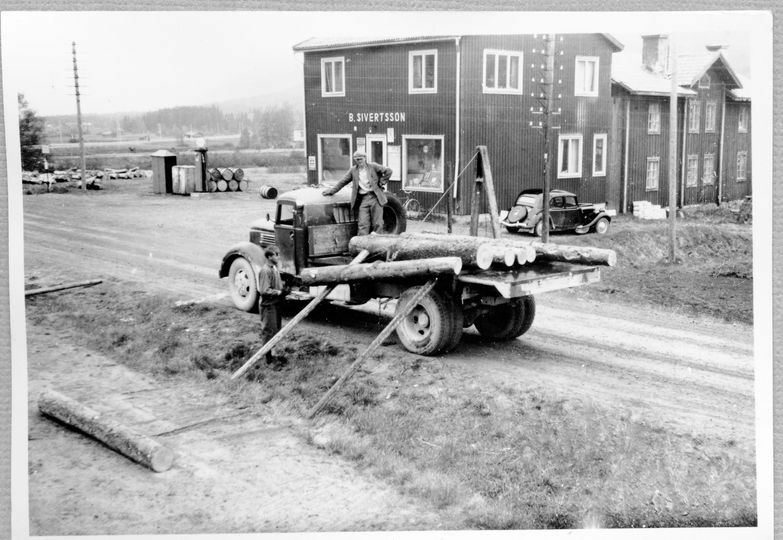

There was probably no significant business here until the beginning of the 1870s. In 1875, Olof Pålsson started a general store. It was later taken over, unknown when, by Brodde Sivertsson (b. 1912) ”Broddes”, and it was closed down in the 1970s. Brodde also had a branch in Sörtjärn.

Jonas Blomqvist’s business began in the 1880s and continued in the hands of his sons and other owners until the 1950s, when it was closed down.

In 1917 a Trade Association was formed in the village and ran for a number of years. It joined forces with other small towns in a bid to make purchases of supplies cheaper. Despite this, it struggled to be profitable and it shut down in 1966. A gas station and general store closed around 2000, and a clothing store was here for a few years. The distance from the railroad, small population and limited income has made trade difficult over the years.

Forestry

The value in the forests for Överhogdal residents before 1850 was mainly the use of the land itself, a place to graze livestock, forage for berries and mushrooms and hunt. Wood in small amounts was used for firewood, timber and leaves etc. were fed to the livestock. When the forest companies began to exploit the forest land in the early 1850s, the forest acquired a completely different value. The trees themselves became valuable.

At the beginning of the 1800s, the division of the woodlands between the crown and the homesteads began in Norrland, so-called partitioning. It was the continuation of a process that began at the end of the 1600s, with the aim of making forests available for the mining industries’ use. The division of land in the 1800s in this area meant that those who owned homesteads were allocated considerable forest areas in the parish free of charge with ownership rights. No one other than those who were then categorized as homeowners received the gift. Crofters, maids, farmhands, craftsmen and others did not count, according to the rules that apparently applied at the time.

In Överhogdal, the partition was carried out in 1874-1887. At that time, almost everyone in the village was connected to agriculture and animal husbandry. But agriculture and cattle farming were dependent on the resources of the forest lands, and for the survival of the homesteads, they needed their summer homes, pastures and access to the marshes and bogs around the village.

In 1852, a contract was signed between the villagers and the James Dickson trading house for logging rights in the parish’s common forests north of Hoan. This was the beginning of the large transfer of ownership to the forest companies and later forest harvesters who today own 87% of the forest assets in the parish. The farmers still had the right to harvest household timber. This timber was usually milled at a sawmill owned by the villagers and was used in the construction of residential and farm buildings in the village. However on the whole, the homeowners’ freedom of action when it came to the timber for household needs was very severely limited by the Dickson contract. And, there were very different views on the interpretation of those contracts.

It became more difficult to farm with these restrictions. A couple of decades later the sawmills on the coast of Norrland began to demand raw materials. Timber became increasingly valuable. When the great forest rush began in Överhogdal in the 1870s, all forest land was owned by farmers. But as the trees themselves gained value, they were sought after by capital-strong companies. Many farmers sold felling rights for 50 years for all forest with a top diameter of 25 cm at a height of 6.3 meters from the root. These are substantial dimensions that can only be dreamed of in the parish today.

Farmers sold their timber rights, but were allowed to live on their home place for the rest of their lives. Former farms were subdivided and either sold or rented out to people who now had other occupations. The creation of the forest industry changed the way the land was used and ended a way of life that had gone on for generations. It was no longer possible to farm in the old ways.

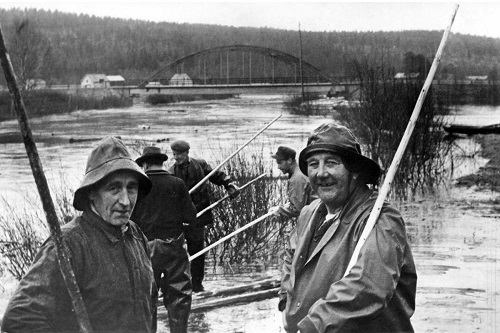

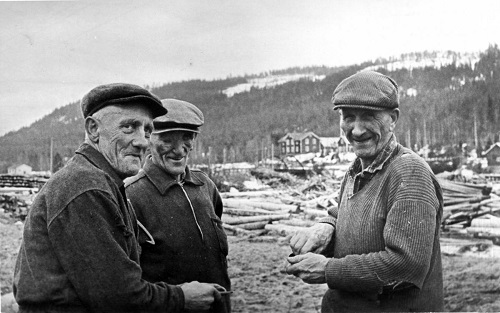

Jobs opened up for forestry workers and other labourers as the farms ceased to exist. The waterways which earlier had been deemed unfit for log rafting were opened up. Logging trails and later roads were established, huts and stables were erected along the watercourses. Long log chutes and dams were built in Hortesån, Långsån and Linån, among other places. Stone coffins were erected by the watercourses to prevent the timber from ending up in the terrain where there were sharp bends. Rafting logs down the river occured until the 1960’s when roads were improved.

The way of life changed rapidly and it is one of the reasons that emigration became something to consider.