General information on emigration

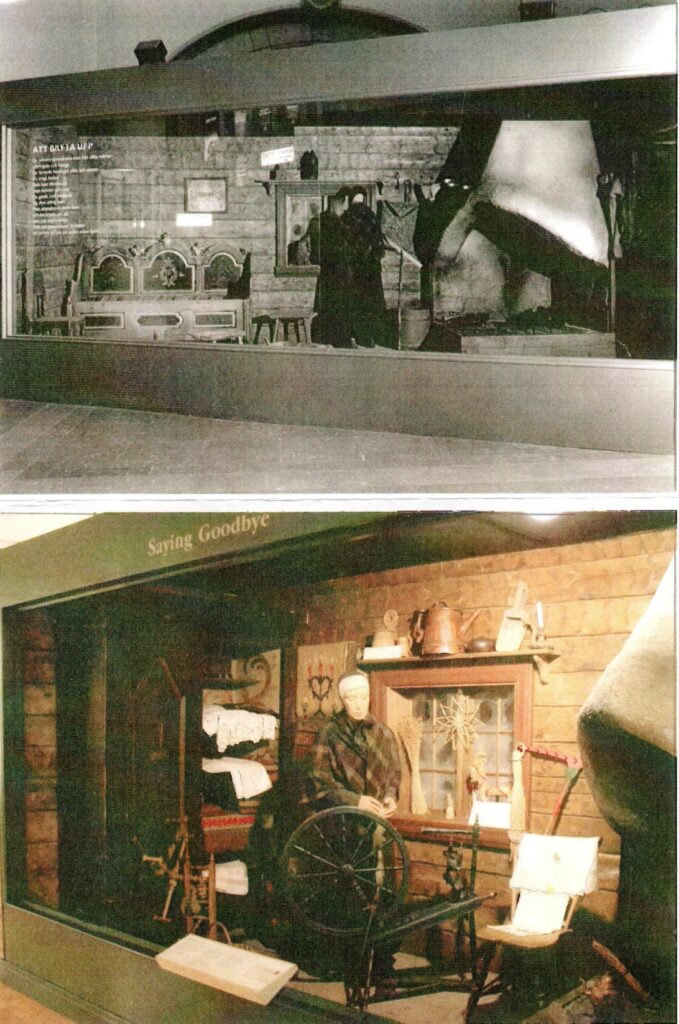

Bottom image: Exhibition in the Swedish American Museum, Andersonville, Chicago, USA, 2010. The props donated by the Nordic Museum.

When the emigrant arrived in the new country, there was no immigration authority to welcome them or help with accommodation. The family itself had to put a roof over their heads before it could establish itself and build a more decent home.

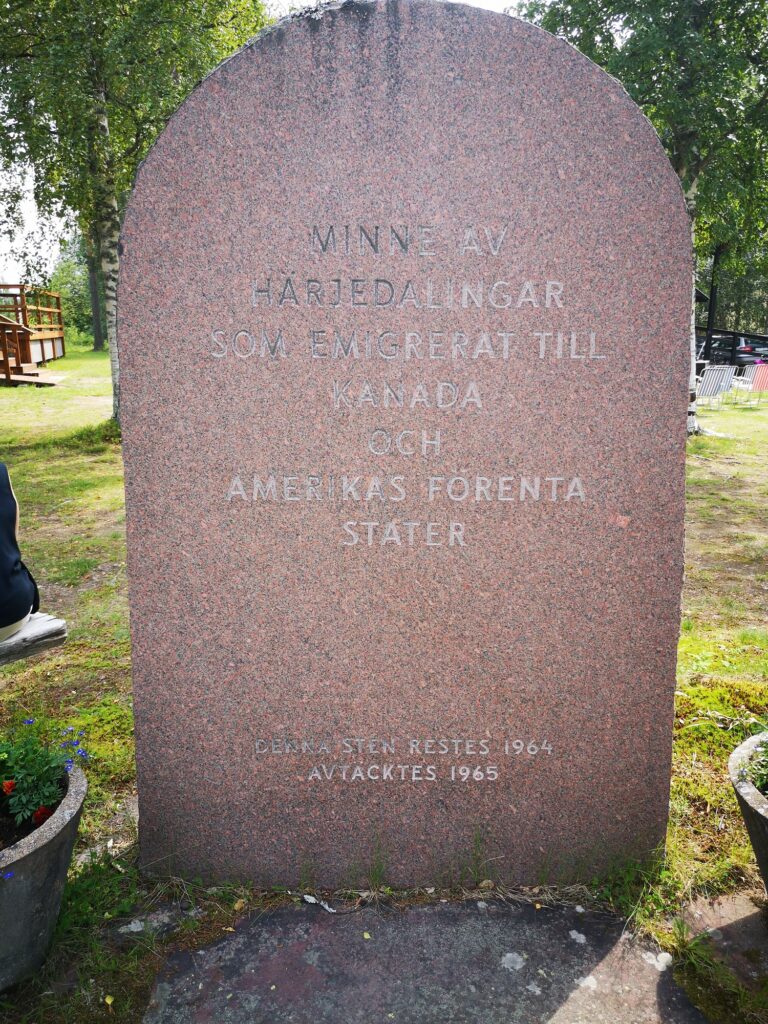

The memorial stone can be found at Sveg’s Hembygdsgård.

Text on stone: In memory of those from Harjedalen who emigrated to Canada and the United States of America.

This stone was erected in 1964 and inaugurated in 1965.

Emigration from Sweden

During the years 1800-1850, the population of Sweden grew from 2.3 million to 3.5 million. During the same period, the peasant class did not often move into the cities, but remained in the countryside. As a result, the rural population grew faster than the total population. The increase was large in all regions, with some such as Norrland experiencing particularly high growth. (Norrland is the Northernmost traditional land area of Sweden, and includes Härjedalen) The consequence was that farms were divided into smaller and smaller units, with less land available to survive on and poorer living conditions for rural people. Despite the division of land, there was not enough land for everyone, causing a devastating increase in landless people within a very short period of time.

There were other trials as well. In western Härjedalen for example there were disputes between mountain farmers and the local Sami. For farmers in the mountain areas, life was arduous enough without disputes with the Sami about pastures.

The Lutheran church had a firm grip on the lives of the rural people in particular. In the mid 1800’s there was an evangelistic awakening with a number of people experiencing a more personal relationship to God. One large movement in the 1870’s saw the creation of the Swedish Mission Covenant Church, a more evangelical Christianity which encouraged study of the Bible and personal Spiritual growth. Other religious groups such as Jehovah’s witnesses also entered the country. The Lutheran church was seen as legalistic and not supportive of these changes, although for the most part there was no outright persecution.

America, promising religious freedom to all as well as a better life looked very attractive in comparison to what they had in Sweden. The shortage of arable land and a lack of tolerance for other religions were probably the reason why the majority of the pioneers who emigrated came from rural areas. Beginning in 1846 until 1929 around 1.2 million Swedes emigrated to North America. Sweden’s population in 1850 was around 3.5 milliion. In 1920 it was 5.9 million. Sweden’s population had increased by 2.4 million between these years despite the emigration. This clearly shows how land hungry many people were during this time.

In 1850 the population of Härjedalen was 6,679 people. From the small village of Överhogdal 138 adults and children emigrated during the years 1867-1930 (the number I counted from the church records).

The main reasons for emigation from Överhogdal were likely the same as mentioned. Farming conditions had always been harsh here with thin, rocky soil, few arable acres and long winters. With the farms being split into smaller and smaller parcels, farming became even more difficult. The majority of the emigrants from Överhogdal however were not land owners. Most were crofters barely scraping by or younger sons of farmers with no hope of getting a farm. Many were labourers, born outside of Härjedalen who had moved here for the work that was available.

The influx of forestry and other workers from other parts of Sweden also brought a broader world view to the the locally raised population, who probably knew little of the larger world before this time. I see a real change in several areas in the later 1800’s. First, the traditional naming practices changed. There were a whole lot of ”new” names given to babies. There also seems to have been a lot more couples having babies before marriage or not bothering to get married. The Church, which had had firm control on the people for years, seems to have lost a lot of its influence with the influx of new ideas and new ways to worship. However, the atmosphere in Sweden perhaps still seemed stifling compared to the freedoms that the USA promised.

Thomas Sievertsson pointed out to me that the majority of emigrants between 1882 and 1890 were members of the Swedish Mission Covenant Church, which was established in Överhogdal shortly before that time. He felt that the church had a visitor, possibly a returning Swede who painted a very rosy picture of life in West, perhaps even suggesting it was a promised land of sorts. Most of those who left during this period settled in Cooperstown, North Dakota and soon established a Mission church there.

Coinciding with all this change was the value their forest land had gained. There was a way for those who owned land to get cash, enabling them to leave. Forestry opened up jobs but conversely, made it very difficult to keep farming in the traditional ways.

The appeal of this ”promised land” in the West and encouraging reports coming from those who first made the move were big pull factors. Ocean travel was becoming more comfortable and taking less time. There are probably no statistics on how many living today have roots in Överhogdal, but it will be in the thousands.

There have been a number of people or groups who have studied emigration in much more depth than I have. Some of the sources Per Göran used are below.

ABF:s emigrant project, Sveg, Sune Månsson

Erik J. Bergström, Glöte – Östersund

Fritz Busk, Lillhärdal

Harry Lundgren, Ytterhogdal

Evert Amundsson, Hede

Yngve Eliasson, Ängersjö

Thomas Sievertsson, Täby

Karlstad emigrant register, Torun Mossfeldt

Emigrant research from Leksand, Stenåke Petersson

Ragunda Emigrant Center, Jan Lindström

I compared the list Per Göran had made to the Church emigration records and found it a close match. The church records found in the Riksarkiv have been the basis of my research. Emigration to North America began in Överhogdal in 1867 and there are emigration records available until 1930. There are some large gaps in time where no one left Överhogdal for America. In seeking the emigrants’ stories, I consulted the church household records and then searched on Ancestry for signs of the new immigrants in either the USA or Canada. In some cases I found lots of information. I have connected with a few families who shared their information and of course, that makes a more interesting story. For others my information is based on the census, marriage, immigration etc. records available on Ancestry. The census records for the USA are available up until 1950 and in Canada until 1931 so this limits information.

For a few of the emigrants, I did not find their paths. In part, this could be because their patronym was too common. There were very many emigrants with the same name and distinguishing between them is difficult, especially for a single male. If a man moved with a family this increases the ability to be sure one is looking at the correct records. The other difficulty is that some emigrants adopted a surname very different from their Swedish patronym.

The newly arrived immigrants did not necessarily stay where they first settled. Many moved around. There are certain places that were ”hubs” for Överhogdal emigrants. I mentioned Cooperstown, but it was not the only American place. The first settlers chose Iowa and Nebraska for their homes. Minnesota, in particular Minneapolis was another hub. As the years passed, many of the settlers moved to other states, in particular, California.

Around 1900 as settlement opportunities opened up in Western Canada, some of the first settlers relocated to Canada, and many of the later arrivals made Canada their destination. The most frequent centres of settlement were farming communities near Camrose and Wetaskiwin, Alberta, near Maple Creek and Humboldt Saskatchewan , and Winnipeg.

If you look at the list of emigrants you will find a few basic details, and a reference to one of the chapters if I know more about them. The chapters are grouped according to where they first settled. For example, you will find information on a family that relocated to Alberta under Cooperstown if that is where they first settled.

The first emigrants left between 1867 and 1869. There was more than a decade where no one left, and then 1882 to 1890 saw a large number leave. Very few left in the 1890’s, but in 1902 the numbers picked up once again. There were few who left in the early 1920’s. In 1929 a large number of young men emigrated, but they almost all returned to Sweden within a few years. This is very likely due to the Great Depression, which they did not realize was about to happen. Life in Sweden became better than life in North America.