.

Landmarks

Landmarks and the Överhogdal tapestries

The village of Överhogdal stretches for about 10 km along the Hoan River in a mostly North-South direction. The river valley is fairly flat, and there are ancient eroded mountains along either side of the valley. If you venture away from the valley itself, the ground is covered in spongy moss, berry bushes and undergrowth. The thing you quickly notice is the many huge boulders left behind by the ice age. It is certainly not land suited for easy cultivation. A mixture of evergreen and birch trees cover the mountain sides.

The Hoan River

The Hoan river runs about 80 km from its mountain origin near Vemhån, and it meanders south and east to the lakes in Ytterhogdal, and then joins up with the larger Ljusnan River near Flor. The Ljusnan then flows to the Gulf of Bothnia. The river is not large but has always had a big influence on the people who live along it. The grass covered flat riverbanks are likely the reason it was settled in the first place. The water is life giving and attracts wildlife as well, but it can also be very destructive. In the summer months it is mostly tranquil as it runs its course. In the Spring with snow melt it can be raging and can overflow its banks. This fast running water was useful when the river was used to transport logs to the sawmills and industries on the coast. However heavy rains can cause flooding at other times of the year as well.

When agriculture was still a big part of life during the 1800s and until the mid-1900s, late summer flooding could have dire consequences as harvests were destroyed. We can imagine it did the same to the earlier settlers and this could have been disastrous to people who were barely scraping by.

Here are translations of the newspaper articles:

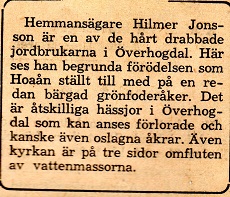

”Homeowner Hilmer Jonsson is one the severely affected farmers in Överhogdal. Here you see him contemplating the devastation that Hoan has wrought with an already harvested green fodder field. There are several haystacks in Överhogdal that can be considered lost and perhaps even the unmowed fields. Also the church is surrounded on three sides by the flooding.”

”The Hoa River threatens to ruin agriculture in Överhogdal. The farmers should seriously consider whether it pays to keep farming. It is Hoaån’s series of deluges this autumn that has brought the misfortune with the river to its climax and the resignation among the farmers is noticeable. Last week, Hoaån flooded, causing the autumn’s third deluge and the village’s farmers believe that they’re on the brink of a total harvest catastrophe right now. Although the water has shrunk in recent days, it will take a huge stretch of dry weather to save the harvest.”

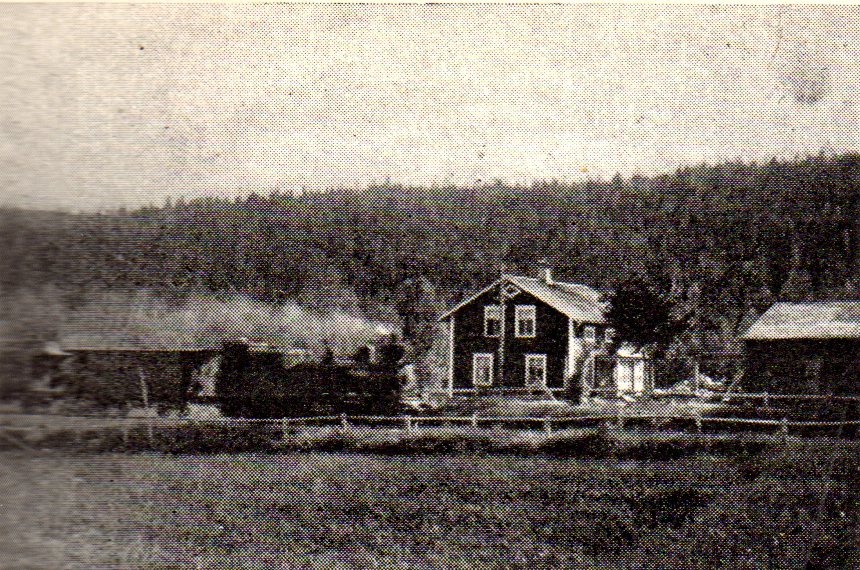

The Inlandsbanan Railroad

Railways were an important transportation link before roads were improved and transport trucks became the norm. There was no railway through Överhogdal until around 1920. There were plans in 1901 to build a railway between Sveg and Brunflo (near Östersund) but the initial plan would be through unpopulated land. Residents from Älvros, Ytterhogdal, Överhogdal and Rätan lobbied against this as the railway was important for them. In the end, they did build a different route. Överhogdal was lucky as the rail actually ran through town. Ytterhogdal, Rätan and Älvros were not so happy as the tracks ran outside of town by about 10 km. In the days before cars became commonplace this was a barrier. The villages felt the railway was never the success it could have been due to this. It certainly did not make their lives easier as they had hoped.

The railway did however provide some employment for Överhogdal residents. It became profitable to turn scrap wood into charcoal. A company called Bergslagen’s iron processing plant used charcoal, and it became a profitable complementary industry next to forestry. There were bridges at the stops along the line to load the charcoal. The industry continued until about 1960 employing about 15-20 people. After 1960 there was a gradual downsizing and hiring freeze with natural departures of staff as the need to charcoal declined.

Inlandsbanan AB today runs 1300 km from Kristinehamn in the South of Sweden to Gällivare in the North. Today it is owned by 19 municipalities and it is used mainly for tourist and freight traffic. Renovations to both tracks and carriages have been taking place on a large scale in recent years, so there is hope the railroad will continue into the future.

The Överhogdal tapestries, The Forngård museum

Överhogdal is a small village in a sparcely settled province but it has a unique claim to fame, for here the Överhogdal tapestries were discovered, and they are one of Europe’s most remarkable cultural treasures. The tapestries are dated to the transition period between the Viking Age and the Middle Ages and are thus among the oldest textiles preserved in our time, and, they are astonishingly well preserved. A myriad of figures wander over the cloth, from right to left. There are animals of various kinds, people, ships, trees and buildings. The images are bearers of a story or stories from another era.

The discovery

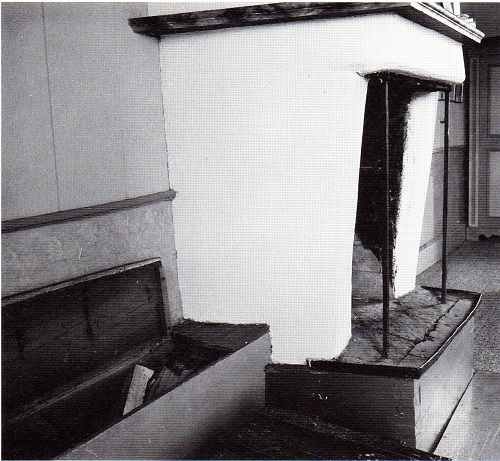

The tapestries are a most remarkable find, and they were discovered at the bottom of a wood box in the church’s sacristy in 1909. The church was undergoing some renovations and clean up, and the churchwarden’s 14-year-old farmhand Jonas Holm was tasked with cleaning out the woodbox. He cleaned out a lot of wood scraps and garbage and at the bottom discovered a bundle of cloth.

Later in the day, the mason Löfberg arrived to do work on the fireplace. He brought his 6-year-old daughter Signe with him, who noticed the material and asked her father for a piece of the cloth because she liked the figures she saw on the material. Löfberg then resolutely cut away a piece that became a quilt for Signe’s doll. When the bricklayer and his daughter went home at the end of the day, one imagines that Jonas faced a decision: burn the bundle together with some of the other rubbish? Fortunately for posterity, Jonas chose instead to store it in one of the church storage sheds.

The following year, 1910, the artist Paul Jonze from Östersund came cycling to the village. He had been commissioned by the then Jämtslöjd Association to look for cultural artifacts of interest from the villages. When he arrived at the Överhogdal church, he looked into the storage shed and saw a crumpled ”rag” among dusty mouldings, wingless church angels and various other debris. Jonze realized that there was something unique lying there in front of his eyes, but he probably didn’t realize that it was almost a 1000 years old!

The village’s schoolteacher Lundmark gave Jonze permission to “borrow” the tapestries and take them to Östersund, where they still are, the crown jewel of the museum Jamtli’s collections. The tapestries, which were sewn together into a quilt in the 14th century, were cleaned in a bathtub in the county governor’s residence by the county governor’s little maid and it is said they smelled quite terrible because of all the dirt that had accumulated over an unknown number of years.

When the tapestries were cleaned, they were hung up in Jämtslöjd’s premises and it was then discovered that some parts were missing. Weaving expert Helena Öberg therefore travelled to Överhogdal the following year, 1911, to try to find the missing pieces and amazingly enough she managed to meet the right people who could lead her to them.

Öberg stepped into the village post office, which was then located in the Ol-Sjuls farm. When asked what her errand was in the village, Öberg replied that she was looking for the missing pieces of the tapestries. An older man happened to be there, who said that if she went to his home, she could see one of the pieces. It was the piece that Signe had received and used as a doll’s quilt. After some persuasion, Signe handed over the quilt to Öberg after being bribed with two kronor (money) and promised a new doll’s quilt, a promise which according to Öberg was fulfilled. The other two missing pieces Öberg found in the church’s sacristy with the help of some craftsmen who were there. Both had been used as rags, one to clean hands and the other to clean the glass of a kerosene lamp.

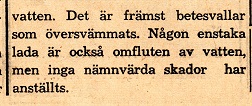

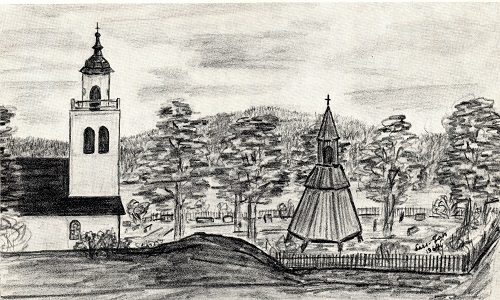

The church in 1910 photographed by Paul Jonze during the ongoing renovation when he visited the village and discovered the tapestries in one of the church halls.

The church was consecrated in 1746, but there has been a chapel here since 1466. However, the tapestries are almost 500 years older. How they have ended up here in our area is a mystery that no one has managed to solve yet, like so much else that concerns the tapestries.

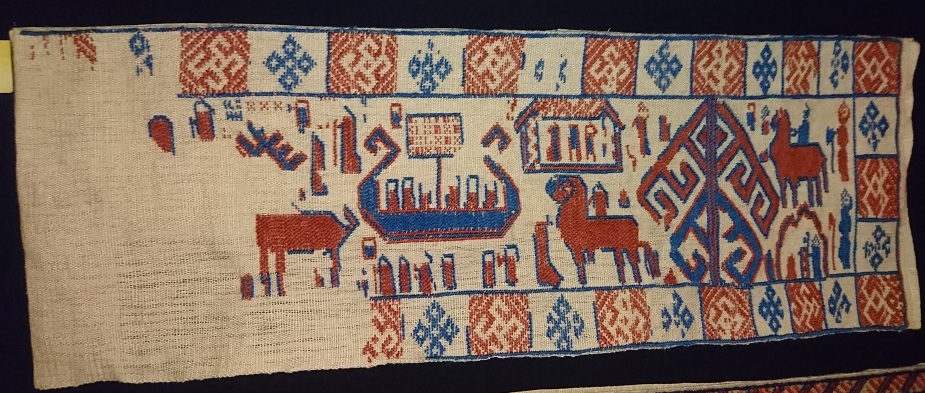

The tapestries themselves are beautiful, covered in throngs of people, animals, ships and buildings that have had experts guessing as to what they are depicting for over a hundred years. What is it that the weavers were trying to convey? Textiles of this kind were a precious commodity that only the rich and powerful could afford. Even then, they were only displayed on festive occasions and hung on the walls in the longhouse. The people who took part in the festivities were probably familiar with the meaning of the figures, but for people today it has so far been a mystery. There is agreement however that they originated in Norway and were not created in Överhogdal or vicinity.

Ever since the 1920s, experts in various subjects have tried to interpret the content based primarily on knowledge of art and textile history, and with more or less credible results. These interpretations were made before we had knowledge of how old the tapestries really are. The result was very fragmentary, interpreting certain figures and building a story around it but omitting the meaning of the other figures. It was not until the 1990s that it was scientifically established using the carbon-14 method that the tapestries were woven sometime during the shift between the Viking Age and the Middle Ages, i.e. between about 1000-1100.

In the past, people interpreted events based on a few images. One idea is that some of the images depict when Christianity came to Norway. Others seem to depict scenes from Viking mythology, such as from the Volsunga saga. Some look like scenes from the book of Revelation, or other Biblical stories.

Staffan Mjöne did his master’s thesis in Archeology around 2010 on the Överhogdal tapestries and his is a comprehensive and detailed attempt to understand the content of the three narrative tapestries. He saw the tapestries as telling one story, and felt that tapestries 2 and 3 have close connections to the stories in Snorri Sturlasson’s Nordic Kings Sagas. He felt that further study on the two parts of the first tapestry would yield more insight into what they portray. He felt that there are a lot of Sami and Germanic objects and symbols as part of the motifs in the third tapestry and that it might express a meeting between the Sami and Vikings.

How these tapestries came to be in Överhogdal is another enigma, and there are several theories that sound credible. Here are a few of them.

Härjedalen was part of the diocese of Nidaros (Trondhiem) in Norway. The bubonic plague (Black Death) around 1350 decimated Europe and Norway lost about half its population. Author Bosse Yman proposed that priests from Härjedelen may have been asked to help in Trondheim. The tapestries could have been given as payment for services rendered. There was no church in Överhogdal at this time, only in Sveg and Lillhärdal so they were not given to an Överhogdal priest. (even when they had their own church, Överhogdal never had a priest of their own). It is strange though that there are no church records of the tapestries, as anything of value should have shown up in the church accounts. However some church records were lost in a fire in Sveg, that could have shed light on the tapestries.

Bosse Yman also described the similarities between the Överhogdal tapestries and a tapestry from Rennebu in Norway, 300 km from Överhogdal. Rennebu is an old Norwegian cultural district dating back to the early Middle Ages. Some of the great men from the Viking Age are buried in mounds here, and it lies along one of the great pilgrimage routes towards Trondheim. There is a stave church here as well which was erected in the 1100s. Some very old articles were found in this old church including a textile fragment, which was suspected to come from the twelfth century. While the actual piece of cloth is missing, there are pictures and good descriptions of the tapestry and it is with the help of these that experts in Rennebu have recreated the tapestry.

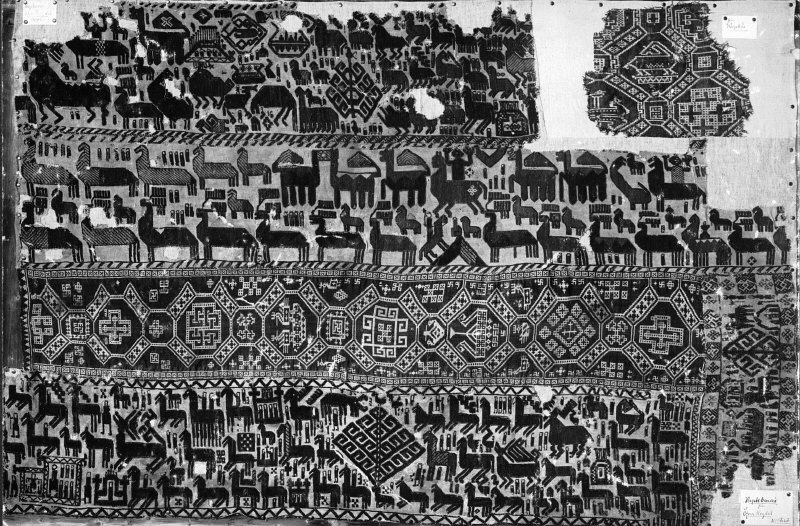

Figures in Rennebuväven are strikingly similar to those found on the Överhogdal tapestries. On the left, you can see some examples.

Another theory that sounds very credible was made by Erik J Bergström. He suggests that the tapestries ended up in Överhogdal in connection with Sweden’s king Karl XII’s ill-fated campaign into Norway in 1718 under General Armfeldt. His theory is that the tapestries could have been brought by returning soldiers from Armfeldt’s army when they dragged themselves home over the border mountains at New Year’s 1719. The hardships of that journey meant death for many Karoliner soldiers.

Armfeldt’s army was in Verdal, Norway at the end of October 1718, about 100 km north of Trondheim by land. The Helsinge regiment in turn was in Vuku, about 20 km from Verdal. According to the order book of October 28, 1718, the general had announced: ”Today at 4 o’clock there will be some tapestries on auction. Those who want to, can attend.”

On 25 November, a Lieutenant Sturm of the Helsinge Regiment found some items hidden in the woods, one of which was a tapestry. The regiment was then located in the area of Melhus and Stören, not far from Rennebu, which as just mentioned has similar illustrations to the Överhogdal tapestries. The Helsinge Regiment had an enormous number of sick people, and no less than 467 men had been sent in October to Stene redoubt (in Norway).

The Helsinge Regiment’s sick were the first to arrive at Överhogdal’s important night camp on 5 January 1719. The regiment’s active but heavily burdened army passed Överhogdal later.

The men of the Helsinge Regiment thus had the opportunity to participate in the auction described above. Was one of the men in possession of the tapestry? Maybe he was wearing it as protection against the cold? Perhaps he died, and the tapestry was brought to the church where it ended up in the shadows of the wood box?

There is a third theory. Some of the Härjedal merchants who traded with both Sweden and Norway became wealthy from their business. An example of this is Olov Matsson from Herrö, near Sveg. He lived in the early 1600s, and did a lot of business with Trondheim and over time became a wealthy man. One of his daughter’s, Brita Olofsdotter, married a man from Överhogdal, Sven Esbjörnsson from the farm Sven’s, who in addition to being a farmer was a länsman in the village for a time and a lay judge. It is possible that a wealthy man like Olov might have acquired the tapestries, then given them to his daughter as a wedding present.

Överhogdals Forngård is the museum that today has a very authentic reproduction of the Överhogdal tapestries and displays that tell their story. Local women wove it over several years. The property also has food service, and offers jewelry, handicrafts and books for sale. Outdoors, a play area has been built with the tapestries as a theme. The Forngård was inaugurated in 1997.

The Överhogdal Museum (Hembygdsgård)

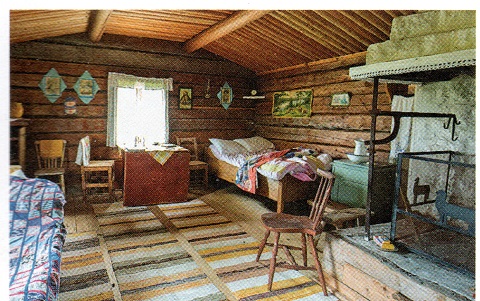

The Gammelbudd homestead was donated by Julia and Olof Ohlin to the local history society in connection with the association’s formation in 1952. ”Budd” previously consisted of two farms, Öster and Väster Budd. (East and West) The current farmhouse, Österbudd, is the only building that remains in its original location. In the past there were two houses, two barns, two saunas, smithies, härbres (storage sheds), stables – a total of 21 buildings. The farmhouse VästerBudd was sold to the Olagården farm after a fire in 1893, when the buildings on the farms Pålsson (”Gunnars”), Olagården and Bjurs were all destroyed.

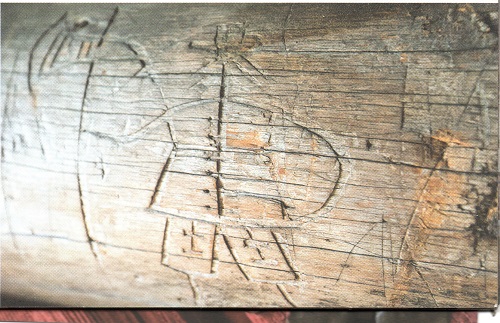

The lower part of the farmhouse is from the 1700s and is a so-called semi-detached cottage. In the mid-1800s, an upper floor was added. You can see from the corners how high the house was before. Other buildings have been moved to this property from different locations. The summer cottage, barn and grain barn are from Lullebuan, the sturgeon cairn from Buddbodarna and the meadow barn from Råberget. In the granary there are some logs with engraved figures – warriors with halbards, (a halbard is a medieval stab and thrust weapon) children, a bride and a date: the 24th of June Anno 1670.

The logs probably came from a large cairn before they became a barn in Holmvallen. One theory is that it was located at a so-called evacuation yard between Sälgåsen and Holmvallen.

A large cairn is a very simple building with a fireplace in the middle of the floor and holes in the roof. Here they made cheese, messmör (soft reduced whey butter) and more.

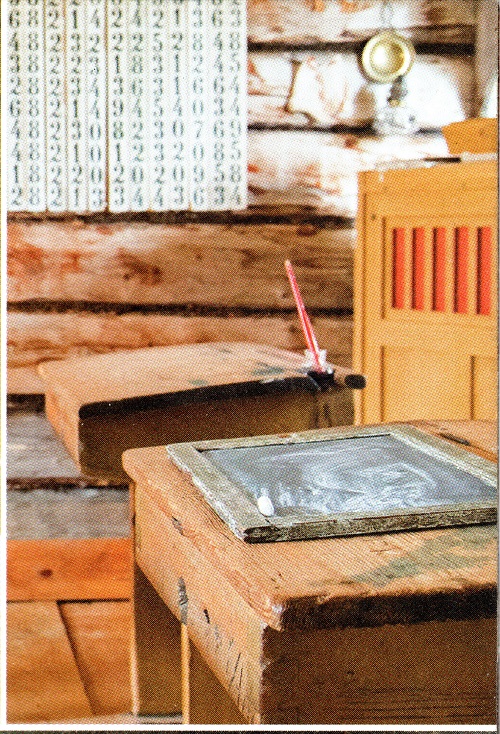

The main house contains centuries-old objects from the area. There are also older clothes and photographs. When Överhogdal’s school was closed, some of the inventory was moved to the museum. The interior of the schoolroom is from the first half of the 1900s.

A driving force that has made it possible for posterity to gain an insight into the conditions of previous generations in our village is Lars Jan Larsson, who deserves a big thank you for his work with the homestead and the village’s history. Lars-Jan was born in what is now Väster-Budd.

Överhogdal’s church

Överhogdal’s first church building was the third to be built in Härjedalen after Sveg and Lillhärdal. It was a simple wooden building with an associated cemetery that was inaugurated in midsummer 1466. The chapel was built by the villagers without the support of the Catholic Church. It was common for churches to be consecrated to a saint and so it was named St. John the Baptist’s Church. At that time, the parish belonged to the parish of Sveg and the diocese of Nidaros.

A new church was reportedly built in the mid-1600s. Possibly a rebuilding may have taken place after the peace of Brömsebro in 1645 when Härjedalen came to belong to the Swedish kingdom.

In 1744-1746 it became necessary to rebuild once again. The current church was built at this time. A separate bell tower was erected on the church property in 1768 and was later demolished in 1851 when the new, bigger bell tower was added onto the church building. This was added in 1849-55 with the ground floor below the tower adding an extension of the main church building. The builder was Johan Nordell from Norrala in Hälsingland. On the eastern gable, a new, larger sacristy of the same width as the church was erected and was provided with windows to the north and south.

Sometime around 1910-13, the church was repaired again and a smaller gallery was built.

In 1949, a thorough renovation was again started, which had to be interrupted due to lack of funds and also because the wood carvings which were removed created new problems as to how to finish the interior of the church.

In 1956, the work resumed once again. The altar was made from the pulpit, which was placed on the north long wall. The beautiful wooden sculptures were then honoured once again. They were made in 1740 by Jonas Granberg from Klövsjö. The exterior of the church retains the character of the 1850s. The number plate and the old altar ring from the 1700s were once again placed in the church. Of the medieval furnishings, only one candlestick remains in the church’s possession, which has become the pole for the altarpiece. A modern candle stand was forged by Erik (Jompo) Lindberg, from Ytterhogdal.The knotted rug in front of the altar was designed by weaver Anna Magnusson from Östersund, and was knotted by the women of the district for the re-dedication of the church in 1957.

The antependium (hanging altar cloth) was designed by Ellen Widén and was woven in 1911 by the weaving teacher Maria Modén Olsson, Jämtslöjd. It is a double weave, a so-called Finn-weave in wool, with motifs taken from the Överhogdal tapestries. It was donated by the Jämtslöjd association to Överhogdal’s parish in 1911.

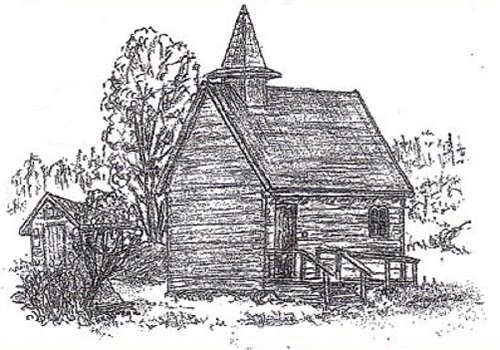

The Swedish Mission Covenant Church

The Lutheran Church replaced the Catholic church in Sweden during the 16th Century following Luther’s reforms. While Luther brought revival in his day, the Church was ritualistic and perhaps seen as lacking in Spiritual life by the mid 1800’s. The church was still very much in control, acting like a branch of the Government in many ways. The Swedish Mission Covenant church was established in 1878 and quickly gained followers. While the core doctrines were not in disagreement with the Lutheran Church, the emphasis was on personal Spiritual growth through recognizing one’s need of salvation, study of the Scriptures, living a God-fearing life and fellowship with like minded believers. While followers weren’t persecuted or banned from the official Church, many felt a stirring for something new. A number of people in Överhogdal joined this new movement.

It is interesting that the great exodus of people from Överhogdal beginning in 1882 until 1890 were mostly members of the Överhogdal Swedish Mission church. Most of them initially resettled near Cooperstown North Dakota and established a Mission Covenant Church in Cooperstown.

A Mission church was erected in Överhogdal in the 1920’s and the building still stands. The building is now owned by a motorcycle club as the church itself closed some years ago.